To Be Free, One Must Play Against the Devices

A Philosophical analysis of Dick Raaymakers’ “Intona: Dodici manieri di far tacere un microfono”

eContact! 21.2 — Dematerialization of the Sounding Object: Conceptual approaches to sound-based artistic practices (July 2023) http://econtact.ca/21_2/belfiore_raaymakers-intona.html

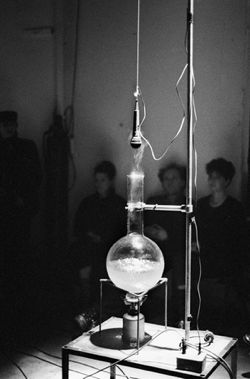

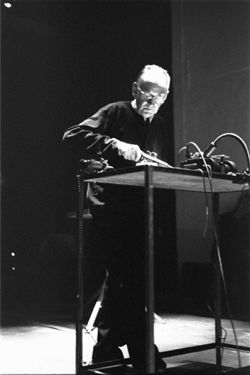

On 17 October 1992, Dick Raaymakers 1[1. Although the spelling “Raaijmakers” is also fairly ubiquitous, here for consistency we will use the Anglicized spelling.] destroyed 12 microphones as a music-theatre piece performed at V2_, an artist collective squat located in ’s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands. 2[2. V2_ moved from Vughterstraat 234 (Den Bosch) to its current location in Rotterdam in 1994.] Around the audience, standing against the walls in a space without a stage, are tables on which various devices, tools and installations are placed (Fig. 1). Over the course of some 25 minutes, Raaymakers, performing his own work, moves methodically from table to table, without expressing any form of theatricality, leaving behind him a series of microphones that have been or are in the process of being destroyed (Video 1). The path that is taken is predetermined and constitutes the compositional plan of the work, and the extreme live amplification of the microphones manipulated during the piece is its only sonic component.

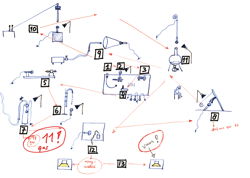

In the space of only a few lines, we have already summarized the basic principles by which the work unfolds. This might seem sufficient to make the essential artistic elements and intentions clear. Indeed, there is no hidden musical structure or choreographic aspect nor is there any form of stylistic ornamentation that a detailed investigation and analysis of the arrangement of the actions performed during the piece might reveal. There is not even really a score to analyze. The documentation directly related to Intona consists of a few photos, a video, a hand-drawn diagramme by Raaymakers (Fig. 3, below) and a short text in a monograph to which the composer contributed.

Here, in contrast to typical approaches to the analysis of musical works, we will proceed alternatively by proposing a philosophical analysis of Intona. This is, however, not an attempt to establish a unified and coherent philosophical theory that could exist separate from the work in question. Rather, the idea is to develop and follow a series of points that will eventually allow an in-depth explanation of the intentions and functioning of the piece. Therefore, our aims are comparable to those of conventional musical analysis: to uncover and communicate the complexity of a thought through one of its realizations. The central question of structure, which often occupies analysts when it can be grasped through the study of musical scores, can certainly not be approached in the same way here. However, we maintain that such a structure exists at the conceptual level. In order to be able to reveal this, the following two sections will lay the foundations for a relevant analytical model.

The first part will consist in establishing that Intona involves not only an explicit discourse as a conceptual work, but also an implicit discourse on art in general. In order to articulate both these perspectives in parallel in the subsequent analysis, we will examine the theoretical writings of Raaymakers as well as those of other theorists and philosophers. To begin, we will consider the title of the work, a clear reference to Futurism. It would appear that Raaymakers has something in common with the Futurists, namely an interest in destruction, albeit in very different proportions and with very different aims, because of his understanding of art as a laboratory that proceeds with models (Fig 1). This first step will allow us to then consider the content of the work in the second part of the text. It will begin with the presentation of a theory of art as play that Intona might imply, of which “destructive” art is the most telling example. This theory will lead to reflections on the explicit discourse of the work that are informed by Raaymakers’ own critique of the microphone. For the purpose of further developing this critique, the notion of the “machinic turn of sensibility” (Stiegler 2016) will prove useful. At the centre of it is the idea that the shift of the viewer’s role from amateur to consumer has been brought about by the development of technological media that channel and/or reproduce perceptions. We will see that Raaymakers proposes in response to play “against” the devices, the details of which will be developed before drawing our conclusions.

An Analysis Model

The subtitle of Intona, translated from Italian, means “twelve ways to silence a microphone.” The video documentation of Raaymakers’ first performance of the work would suggest that one of its æsthetic principles is a form of minimalism. Indeed, it seems that nothing more than the bare minimum is implemented to “silence” the microphones present during the performance. As Joke Brouwer and Arjen Mulder write in their monograph on Raaymakers, “a few techniques are tried and listed. … All these actions are carried out on a purely practical level….” (Brouwer and Mulder 2009, cited in V2_ n.d.)

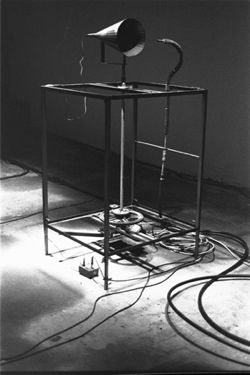

The æsthetic aspect of the work is very raw and not necessarily experienced as something that is “musical” by the audience. Thus, there is a minimalism in terms of the means and æsthetic experience that seems to function as a sign indicating there is more at stake than the situation taking place on the stage (Fig. 2). This assumption is confirmed by the short note presenting the event on the website of the V2_ association in which facilities the work was created:

On 17 October 1992, Raaijmakers performed a musical and theater piece entitled Intona. … Through it, Raaijmakers made indirect statements about specific technologies by dissecting the 12 microphones; especially about reproduction techniques in new media, and about the microphone in particular. (V2_ 1992)

A certain “æsthetic poverty” combined with the ambition to make “statements”, albeit indirect, seems fairly typical of work that we might describe as conceptual. The notion is, however, rather vague and encompasses in reality a wide variety of practices. Indeed, there might be as many perspectives on it as there are conceptual artists. We need only examine the better-known works of such members of the historical “movement” of conceptual art as Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt, Lawrence Weiner and maybe also Joseph Beuys, who have all in their own way emphasized the extreme importance of the “idea” in their practices. Generally speaking, the idea would relate to their artworks no longer only as a necessary part in the creative process, but also as an integral part of the works’ artistic content. Here we might consider LeWitt’s Wall Drawings, which he has others paint on the basis of verbal instructions, or the ephemeral situations documented by Huebler, as well as Kosuth’s “representational triangulations” when he counterposes object, image and definition. However, it is clear that not all artists have the same notion of “ideas” and assign them the same importance with regard to their concrete manifestation. Moreover, their works seem to have very different functions and purposes. Because of these disparities, it would seem necessary to find a definition of conceptuality that is not artist-specific. This would also allow us to consider conceptual art more broadly as an artistic technique rather than as a watershed moment in the history of Western modern art and thus to propose a model for the functioning of Intona in particular.

Such an approach to the definition of conceptuality can be found in philosopher Harry Lehmann’s work. In his conference Conceptual Art and Conceptual Music, he proposes as the structure of conceptuality that which he designates an isomorphism between “concept” and “percept” (Lehmann 2019, 7:40ff).

A concept is understood here in the sense of a verbal indication that not only indicates how to produce a work of art, but also how to perceive it. Nevertheless, this concept is not necessarily made evident through the description, presentation or performance of the work: in addition to being a plan, an outline or a description of a work, the “concept” itself may be obscured behind its title or even implied or situated at the level of the general practice of the artist. This concept is linked to a “percept” (which here means simply the sensation evoked by the work in the mind of the receiver) by a particular relation of isomorphism which imparts to the work its conceptual nature. It is a question here of a sharing or of a conservation of form, of structure between the two terms, between which there is a “one-to-one” relation. The special nature of this relation is that the receiver would be able to recognize and understand the concept from which the work comes, as such a work is neither more nor less than the idea of it “manifested” in a concrete form. In this sense, it is clear that conceptualism can be considered as a form of minimalism (Kreidler 2019, 25).

Lehmann gives a classic example of a work that can be understood anachronistically as conceptual because of its structure: Kasimir Malevich’s Black Square, an avant-garde work from 1915. The reference of the title is in a certain way “isomorphic” to the object that is presented, at least in the sense that the painting is neither more nor less than a black square. The receiver, knowing the name of the painting, is then able to understand it as a manifestation of the idea of a black square — and not of any other idea that could also be realized in a similar form. 3[3. We might contrast Black Square with the caricatural monochromes of Alphonse Allais (1854–1905) published in 1897 as Album primo-avrilesque. The titles of the pages consisting of one solid colour, written just underneath the coloured area, describe situations involving subjects of a similar colour, with the superposition of these objects supposedly making the individual elements indistinguishable. For example, Allais’ black monochrome is described as representing “Negroes fighting in a cellar, at night”. Dubious and outdated perspectives on race aside, the two works hold distinct identities, despite each being an artwork consisting of a black, four-sided geometric shape (ideally framed and hung on a gallery wall).] Although Lehmann’s model is questionable in several respects, it is interesting because it does not overestimate the concept at the expense of the realization. In this sense, it also allows for a dynamic, “transductive” understanding of the conceptual creation process rather than the static and “deductive” model proposed by LeWitt in his Sentences on Conceptual Art (1968), which in practice seems too rigid:

If the artist changes his mind midway through the execution of the piece he compromises the result…. Once the idea of the piece is established in the artist’s mind and the final form is decided, the process is carried out blindly. (LeWitt 1968)

Looking at Intona in more detail, it seems possible to say that the work comprises an isomorphic relationship between a performance and a verbal idea that is mainly made known through a reading of the subtitle of the work. Raaymakers’ hand-drawn diagramme for the realization (Fig. 3) does not constitute a score of the work but rather a partial representation of a concept, in the sense that the piece is unplayable without being accompanied by some form of verbal transmission — if only to indicate how to destroy the microphones. As an example, a reconstruction of the performance could be made by simply reading and executing the captions accompanying the photo documentation of the event (Brouwer and Mulder 2009, 260–273), which could function — ex post facto — as its “score”:

[1] Drilling: a microphone’s housing is drilled open by a miniature electric hand drill.

[2] Dismantling: a microphone’s membrane is removed with a small surgical knife.

[3] Sawing: a microphone is sawn in half with a miniature jigsaw.

[4] Grinding: half of a microphone is ground away with a heavy grinding machine.

[5] Burning: the front of a microphone is slowly pulled into the blazing flame of a gas burner until it is completely charred.

[6] Dissolving: a microphone’s membrane is dissolved by methylene chloride drip.

[7] Immersion: a microphone hangs in a container that is slowly filled with water until the microphone is completely submerged.

[8] Flattening: a microphone is crushed excruciatingly slowly by a specially constructed flattener.

[9] Blowing: a microphone’s membrane is blown away by concentrated 3-bar stream of compressed air.

[10] Crushing: a microphone and a playing Walkman are placed on a slab of concrete and crushed in one blow by a falling 45-pound [20 kg] metal weight.

[11] Boiling: a microphone is slowly lowered into a glass distillation flask filled with boiling water.

[12] Exploding: the head of a microphone is blown up with explosives.

The performance ends with the burning of the two large, loudspeakers that have transmitted the sounds of the microphones.

This reconstruction can be considered as the piece’s concept in the strict sense proposed by Lehmann. Indeed, we might propose that a conservation of form is maintained between the thirteen steps described and the original performance. If this is true, we could reasonably expect that a subsequent execution of these instructions would lead to a valid and recognizable performance of Intona. Of course, during Raaymakers’ performance, some of the actions had different durations and were executed in parallel, making the situation more complex than its mere description might suggest. Moreover, it is inevitable that the interpretation of the piece will vary from one occasion to another, resulting in a yet wider range of potential variations. The isomorphic relationship proposed by Lehmann might nevertheless be unaffected by this, as long as the order of actions and their content remains unchanged. After all, if the verbal instructions proposed for the performance of Intona are adequate, they are not essentially different — in terms of their role and function — from those of LeWitt’s Wall Drawings, which are considered historical examples of conceptual art:

Each wall drawing begins as a set of instructions or a simple diagram to be followed in executing the work. … [T]hese straightforward instructions yield an astonishing — and stunningly beautiful — variety of work that is at once simple and highly complex, rigorous, and sensual. (MASS MoCA 2008)

Lehman’s isomorphic relation does not, however, provide us with a complete model of the functioning of conceptual works. For example, it is difficult to find the articulation between the work’s (hypothetical) practical instructions for Intona’s realization and Raaymarkers’ discourse (his “indirect statements”) supposedly embedded in the work. In fact, Lehmann’s problem is that he oversimplifies the structure of the concept. Even the black square is the product of multiple decisions and therefore ideas, especially with regard to the choice of canvas, its dimensions or even the type or tone of paint (or other medium) used to cover it. From this point of view, Intona can also ultimately be understood as the result of a cluster of more or less related artistic decisions. One of LeWitt’s Sentences, despite the obvious divergences between it and Lehmann’s approach, is helpful in this regard:

The concept and idea are different. The former implies a general direction while the latter is the component. Ideas implement the concept. (LeWitt 1968)

Clearly there are a number of elements forming Raaymakers’ project. On the one hand, there is a general direction, a “vision” of the work, and on the other hand, a variety of ideas that are necessary for the work to be brought into existence. The relation of the work to its concept becomes more complex. If there is an isomorphism, it is between the ideas (in the sense of LeWitt) and the percept; as for the concept, it becomes more abstract. It approaches what might be considered the “discourse” of the artist, or is at least a part of it. There is thus another relation to acknowledge, this time between the ideas and the concept in terms of the preceding quote: that of “relevance”.

It then becomes possible to determine and define the criteria required to assess and evaluate a work such as Intona. In addition to the more or less satisfactory isomorphic relation between the “plan” and presentation of the work it is important to consider the relevance between the ideas and the concept of the artist that they implement. One could propose that this is in fact where the talent of conceptualists lies, and where an analysis such as we aim to make is useful.

The Post-Duchampian Artist as Philosopher of Art

Historically, the writings of some conceptual artists reflect a desire to not only describe and position their own individual works, but also to define art itself. For example, for LeWitt: “The conventions of art are altered by works of art” (LeWitt 1968). And Kosuth: “Artists question the nature of art by presenting new propositions as to art’s nature” (Kosuth 1969). If Adorno’s general proposition that “artists are always also at work on art and not only on artworks” (Adorno 2002, 181) is true, it is even more so for conceptual artists, in the sense that this defining of art becomes a fundamental part of the process of developing and executing each individual work. Indeed, and it has been said elsewhere a great number of times, the artwork’s virtualization from a material occurrence to a mental process — an act that was initiated by the avant-garde and culminated in the readymades of Duchamp — has advanced a concept of art uncoupled from any specific medium. With artists now able to transform not only materials but also ideas into artworks, they must be able to justify their choices of which “medium” — tangible or not — or combination of mediums to use. And this applies equally to new as well as traditional media configurations. For Kosuth, for example, “[t]he ‘value’ of particular artists after Duchamp can be weighed according to how much they questioned the nature of art….” (Kosuth 1969) Indeed:

Being an artist now means to question the nature of art. If one is questioning the nature of painting, one cannot be questioning the nature of art. If an artist accepts painting (or sculpture) he is accepting the tradition that goes with it. That’s because the word art is general and the word painting is specific. Painting is a kind of art. If you make paintings you are already accepting (not questioning) the nature of art. One is then accepting the nature of art to be the European tradition of a painting-sculpture dichotomy. (Kosuth 1969)

The question, however, is not whether or not to agree with Kosuth on the superior value of so-called “general” art in regard to its traditional “subordinate” practices. The quote seems relevant here because it exemplifies the rather common idea that artists working since the historical episode of “dematerialization” or “de-specification” of the work of art are expected to be able to justify their position regarding the “new” nature of art. In this sense, it means that artists are understood to be expressing implicitly in their practice or explicitly in their speech the result of a conceptual activity that consists of a definition of art that is simultaneously relevant to and formed in one’s own practice.

In summary, the conceptual work has a specific articulation: a perceived work corresponds to a complex of ideas of which it is the or one of the most “isomorphic” implementations. This complex of ideas is itself linked to a more general discursive concept by a relation of “relevance” that can be articulated only when the concept of the work is made clear. Finally, the conjunction of the specific ideas (implying the material, for example) of the discourse and of their articulation allow a generalized conception of art to appear in the work itself.

This rather substantial introduction has made it possible to lay the foundations of the analysis that follows. The isomorphic relationship between Intona’s “ideas” and its performance, which in a way serves as a hypothesis in this text, will allow us to address Raaymakers’ discourse and to see how it relates to the ideas encoded in his work. We will then see how these ideas imply a specific model of art. To begin the analysis properly, we should first examine the work’s title.

Intonarumori

The title of the work, as well as perhaps the use of Italian for its subtitle, is a reference to the musical-sonic work of the Futurist painter Luigi Russolo.

In his manifesto “L’Arte dei Rumori” from 1913, considered one of the founding texts of the sonic avant-garde of the twentieth century, he calls for the construction of instruments that would make it possible to “replace the limited variety of timbres offered by contemporary orchestral instruments with the infinite variety of the timbres of noises, reproduced by suitable mechanisms.” (Rainey, Poggi and Wittman 2009, 138) These mechanisms, able to create “sound-noises” having “a general predominating tone among its irregular vibrations, a sufficiently wide variety of tones, semitones, and quarter-tones” (Ibid.) are called “intonarumori”. Russolo derived this compound Italian name from the third person conjugation of the verb “intonare” (one of which meanings is “to set the voice at the right pitch… to tune an instrument or its various parts… according to the correct or desired intonation” 4[4. Our translation of the definition of “intonare” on Treccani: “Mettere in giusto tono la voce…; accordare uno strumento o le varie parti di uno strumento… secondo la giusta intonazione o nell’intonazione voluta….”]) and “rumori” (“noises”). We will return later to examine in more detail the connection between Russolo’s instruments and Raaymakers’ work.

A casual etymological analysis of the Latin roots of the segments of “intona” offers further interesting perspectives: it could be seen as a construction of the preposition in and the verb tona. The former means “inside” or “within” but is also used as the prefix in- to indicate negation; the latter is the second-person form of the present active imperative of the verb “tono” (the first-person form for: I thunder, speak thunderously or resound like thunder). A multilayered instruction can thus be inferred from the title: to make (a) sound enter while simultaneously denying its existence. With a slightly open mind, one could consider this an extremely reduced formulation of Raaymakers’ concept.

However, the relationship between Futurism and Intona should be examined in more detail (Fig. 4), as it is only very superficially addressed in the programme notes for the work. Indeed, Brouwer and Mulder do not position it beyond a simple mention of the Futurists, nor can any further information be found elsewhere about the specific connection between Intona and this artistic movement. But, as we seem to have established the specific importance of the title to an eventual understanding of the work, it is relevant to also explore Raaymakers’ reference to the movement. To do so, we can begin by addressing a common theme to Intona and the Futurists’ ideas: destruction. This, before clarifying the composer’s discourse completely, will lead us to develop the vision of art that Intona seems to embody.

The Destructive Character

Raaymakers published a book in 2011, The Destructive Character, in which he developed a theory of the destructive act in all types of Art. At first glance it comes across as curious that this publication, nearly 20 years after Intona, makes no mention of the work — even though it seems to be Raaymakers’ “destructive” piece par excellence (Fig. 5). Looking at the chronology in more detail, it is possible that some of his writing coincided with Intona’s development. Indeed, in a letter from 2004, Raaymakers writes the following about the re-performance of Pianoforte, one of his early works:

Bringing this primal child literally back to life, more than forty years after, gave me the idea to glue back together the shards of the dismantled and fragmented story from 1992 on the relation between destruction and art and to republish it under the title “The Destructive Character”. (Raaymakers 2011, 5)

It is possible that Raaymakers had simply not modified his 1992 drafts, which could mean that Intona was omitted because no performance instructions or documentation existed yet (apart maybe from a diagramme made by the artist [Fig. 3]). In any case, there’s a thematic overlap between Intona and The Destructive Character that makes its mention and examination highly relevant in this context.

The title of the book is a direct reference to a short eponymous text by Walter Benjamin 5[5. Walter Benjamin, “The Destructive Character,” Frankfurter Zeitung, 20 November 1931. Available in Punkto 2 (May 2011) “Destruição” [Accessed 8 May 2023].], on which Raaymakers’ own text is based. Benjamin’s essay is included in the book as a “Preface” to the composer’s text. It consists of short sentences that attempt to define what Benjamin calls the “destructive character”. It is not clear, however, whether we are talking about one psychological aspect among others in a subject, a general disposition, or an intersubjective social phenomenon, because the remarks in it seem to be relevant in all cases.

There is a kind of “triangulation” between Raaymakers’ text, his artwork and the Futurists. It seems interesting to compare Benjamin’s text with, for example, the first Futurist Manifesto 6[6. Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “Futurist Manifesto,” originally published in French in Le Figaro [Paris], 20 February 1909.], in order to give an idea of the “discursive context” in which Intona is likely to be embedded. An in-depth analysis is not necessary for this. By interlacing a sequence of excerpts from the two texts it is possible to get a fairly clear idea of the deeply destructive nature encountered in this avant-garde movement:

[Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Futurist Manifesto] Up to now literature has exalted contemplative stillness, ecstasy, and sleep. We intend to exalt movement and aggression, feverish insomnia, the racer’s stride, the mortal leap, the slap and the punch. (Cited in Rainey, Poggi and Wittman 2009, 51–53)

[Walter Benjamin, The Destructive Character] The destructive character is always blithely at work. It is Nature that dictates his tempo, indirectly at least, for he must forestall her. Otherwise she will take over the destruction herself. (Cited in Raaymakers 2011, 9–10)

[FTM] We stand on the last promontory of the centuries! … Why should we look back over our shoulders, when we intend to breach the mysterious doors of the Impossible? Time and space died yesterday. We already live in the absolute, for we have already created velocity which is eternal and omnipresent.

[WB] Really, only the insight into how radically the world is simplified when tested for its worthiness for destruction leads to such an Apollonian image of the destroyer. This is the great bond embracing and unifying all that exists. It is a sight that affords the destructive character a spectacle of deepest harmony.

[FTM] We intend to glorify war — the only hygiene of the world — militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of anarchists, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and contempt for woman.

We intend to destroy museums, libraries, academies of every sort, and to fight against moralism, feminism, and every utilitarian or opportunistic cowardice.

[WB] The destructive character stands in the front line of traditionalists. Some people pass things down to posterity, by making them untouchable and thus conserving them; others pass on situations, by making them practicable and thus liquidating them. The latter are called destructive.

[FTM] The oldest of us is thirty: so we have at least a decade left to fulfill our task. When we are forty, others who are younger and stronger will throw us into the wastebasket, like useless manuscripts. — We want it to happen!

They will come against us, our successors….

The oldest of us is thirty: and yet already we have cast away treasures, thousands of treasures of force, love, boldness, cunning, and raw will power; have thrown them away impatiently, furiously, heedlessly, without hesitation, without rest, screaming for our lives. Look at us! We are still not weary! Our hearts feel no tiredness because they are fed with fire, hatred, and speed!

[WB] The destructive character is young and cheerful. For destroying rejuvenates, because it clears away the traces of our own age; It cheers, because everything cleared away means to the destroyer a complete reduction, indeed a rooting out, of his own condition.

Even after only a few excerpts, it becomes fairly clear that the Futurists have important points of convergence with the “destructive character” described by Benjamin. But their ideas are only one manifestation among others: a mere exemplification of destructiveness need not be as ideologically unacceptable as that of Marinetti.

Nowadays, it is indeed rather surprising to see a work referring to this notoriously colonialist, misogynistic, war-exalting movement, which later had links with fascist Italy that were ambivalent, to say the least. Perhaps the Futurists can be seen as exemplifying in this sense the destructive character instantiating itself unconditionally in art and life. The Futurists’ objective was not only to find and exploit new forms of expression but also to complementarily instigate a total anthropological revolution, at the centre of which aggressiveness, violence and speed would be the driving forces. As proof of these intentions, we need only peruse the variety of subjects treated by their manifestos: not only all the arts, architecture, urbanism and fashion, but also sexuality, cooking, perfumery, typography and politics, among others (Lista 2015, table of contents). In this sense, Raaymakers explicitly diverges from the Futurists in their abusive conflation of art and life:

[A]rt had to make a link with reality, without getting too much involved or over-identifying with it. (That the danger of a certain over-identification is not merely imaginary, was proven by some fanatical futurist artists who in 1914, driven by an overstrained sense of things, actually entered the First World War, never to return). [Raaymakers 2011, 76]

In a way, the tone of the reference between the title of Raaymakers’ work and the Futurists is difficult to understand. Is it irony? Is it a tribute? A form of détournement? What we can say is that the conception of destruction — or, in other words, the manifestation of the destructive character — is very different for Raaymakers. The separation between art and reality that he talks about allows us to address exactly how his understanding of art differs from theirs and the consequences that this has on his artistic practice (Fig. 6).

Destruction, Art and Play

Early on in The Destructive Character, Raaymakers makes the following remark:

In our society… destruction is always condemned. Always, but not all manifestations of it! Its nicest, and also most innocent forms are associated with “celebration” and “games”. (Raaymakers 2011, 18)

He then proceeds to give examples such as fireworks, or different games such as “tin can toss”, where piles of objects must be destroyed by throwing a ball. We could easily find more examples for his list. On the one hand, there are innumerable examples of popular audiovisual entertainment products such as TV shows, movies or video games that depict scenes of extreme destruction. For example, it is not uncommon in today’s blockbusters to encounter fights between monsters, robots or superheroes that result in a literal levelling of the centre of a metropolis. On the other hand, there is no shortage of examples of musicians or bands destroying their instruments by force or even by fire, at the end of their concerts (Fig. 7). Indeed, within these specific contexts, such destructive practices have become so common that they are essentially expected by the viewers; more unexpectedly, the burning of a piano is even part of military ceremonies in some countries. 7[7. See, for example, the “Ceremonial piano burning” section in the Wikipedia article on “Piano burning.”]

One thing that these disparate examples have in common is that that they are each in their own way encountered in the margins of our everyday life. In his famous book Homo Ludens, historian Johan Huizinga considers that culture, which includes, among others, the ludic, religious / ritual and artistic spheres mentioned above, was originally about play. The primordial play, as a function of conscious living beings (Huizinga 1974, 7), then precedes culture and has several fundamental characteristics. First of all, it is a free action, in the intuitive sense of “free time” — i.e. it is voluntary; it is neither compulsory nor essential to our existence. Thus, play — beyond its role in early childhood development, where it provides a perhaps biological function facilitating physiological as well as cognitive development — is not necessary for the realization of the primary needs of the adult; it is not directly “useful”. Moreover:

A second characteristic is closely connected with this, namely, that play is not “ordinary” or “real” life. It is rather a stepping out of “real” life into a temporary sphere of activity with a disposition all of its own. (Huizinga 1974, 8)

In addition to these two main characteristics, there is the idea that the game always takes place in a specific space and time, separate from everyday life. Within these limits, a particular and absolute order is established through rules that may differ radically from those of “real life”. If the order is broken, the “world” created by the game disappears. Although it is connoted as something associated with joy, with non-seriousness,

the consciousness of play being “only a pretend” does not by any means prevent it from proceeding with the utmost seriousness, with an absorption, a devotion that passes into rapture and, temporarily at least, completely abolishes that troublesome “only” feeling. (Huizinga 1974, 8)

This is primarily valid for the player, but it also seems to be relevant to the spectator. Indeed, when we consider elite sports, for example, it is immediately obvious that pleasure, entertainment, seriousness and politics are completely intertwined and that enormous sociocultural interests are at stake just at the level of their mediation, not to mention the complex infrastructures that are essential to their existence. Huizinga then uses these basic considerations to build up a general theory of culture sub specie ludi, in which art is treated in an extensive way. The project of Homo Ludens is to show that culture (and thus the art that derives from it) is genealogically linked to ludic practices and that it includes elements of play. In this theory, however, a certain ambiguity is always present. Can something that has a playful element be considered a game? In other words, does an activity like sport turn from an innocent game into an institution of which only some of its features, but not the profoundly playful nature at its base, have remained? A partial answer to these queries can be inferred from remarks made by Ludwig Wittgenstein in the first part of his Philosophical Investigations:

Consider for example the proceedings that we call “games”. I mean board-games, card-games, ball-games, Olympic games, and so on. What is common to them all? … [I]f you look at them you will not see something that is common to all, but similarities, relationships, and a whole series of them at that. … Look for example at board-games with their multifarious relationships. Now pass to card-games; here you find many correspondences with the first group, but many common features drop out, and others appear. When we pass next to ball-games, much that is common is retained, but much is lost. — Are they all “amusing”? Compare chess with noughts and crosses. Or is there always winning and losing, or competition between players? Think of patience. In ball games there is winning and losing; but when a child throws his ball at the wall and catches it again, this feature has disappeared. Look at the parts played by skill and luck; and at the difference between skill in chess and skill in tennis. Think now of games like ring-a-ring-a-roses; here is the element of amusement, but how many other characteristic features have disappeared! And we can go through the many, many, other groups of games in the same way; can see how similarities crop up and disappear.

And the result of this examination is: we see a complicated network of similarities overlapping and criss-crossing: sometimes overall similarities, sometimes similarities of detail.

I can think of no better expression to characterize these similarities than “family resemblances”…. (Wittgenstein 1999, 31e–32e)

What Wittgenstein highlights is that it is impossible to give a definition of play that allows us to distinguish it from non-play in all instances. Some form of “investigation” needs to be carried out in order to understand what common elements different practices have in order to decide in what sense they could be considered a game in a network of similarities. So, although cultural importance and meanings change at different stages of sophistication or temporal extension in cultural development, we are still dealing with games. Indeed, such considerations led Wittgenstein to consider the whole of our symbolic activity as a network of games.

Nevertheless, to say that “art is a game” in the sense of it being a single game is, according to the considerations that we have just made, wrong. In order to lend credibility to this “non-definition” it would perhaps be more correct to say then that artistic practice operates in the ludic sphere — which can therefore embed a theoretically indeterminate number of different practices. From this perspective, the arts would be understood rather as a sub-network of the ludic sphere. Many points would need to be clarified in order to formulate a convincing theory of art on the basis of these brief reflections; however, these few remarks are enough for us to proceed.

We can now examine the ways in which art-as-play functions as well as its relationship to the real world, from which it is in some ways separate. It is in this respect that Raaymakers’ relationship to destruction is fundamentally different from that of the Futurists. Of course, what has been said about play could perhaps be applied to all art, but what is special about art involving destruction (Fig. 8) is that it shows the necessity for art to involve a certain form of artificiality. Indeed, to take an extreme example, not even the most radical body art artists have gone so far as to commit suicide in the context of their works. Despite the extremism present in some of these practices, for Raaymakers art proceeds nevertheless according to models: “By means of constructing models for artistic destruction, art could measure up to reality, or, better put, ‘measure’ reality” (Raaymakers 2011, 76). This can be compared with Marshall McLuhan’s conception of the functioning of games as “dramatic models of our psychological lives” (McLuhan 1994, 237). He joins Huizinga in saying that they are separated from life and “enable us to stand aside from the material pressures of routine and convention, observing and questioning” (Ibid., 238). He goes on to distinguish the function of the ludic and artistic spheres:

Art is not just play but an extension of human awareness in contrived and conventional patterns. Sport as popular art is a deep reaction to the typical action of the society. But high art, on the other hand, is not a reaction but a profound reappraisal of a complex cultural state. (McLuhan 1994, 241)

Under these conditions, the artist creates situations in which “models” of reality are created and contemplated — Raaymakers speaks of “laboratory scale” (Raaymakers 2011, 76). There is thus an idea of separation and judgement that we also find in the meanings of the Ancient Greek verb krinein (κρίνειν, “to separate”, “to divide” or “to judge”) — to which we owe our term “critique”. This reduction allows art to be a means of not only individual but also collective communication:

[A]rt, like games or popular arts, and like media of communication, has the power to impose its own assumptions by setting the human community into new relationships and postures. (McLuhan 1994, 242)

This is how McLuhan ends up saying that games “are a kind of talking to itself on the part of society as a whole” (McLuhan 1994, 242).

Faithful to his famous adage “the medium is the message,” he considers that it is the general model of the game, or the performativity of the medium’s particular configuration, that counts in the transmission of the sensory information of art more than the explicit content of the work. He adds that “approaching a painting or a musical composition from the point of view of its content… is guaranteed to miss the central structural core of the experience” (Ibid.). Depending on the specific notion of “content” we subscribe to or consider, this might at first sight seem to directly contradict the essence of the present discussion. It seems self-evident that a relevant and meaningful account of the experience of Richard Strauss’ Alpensinfonie op. 64 could never be gained by simply talking about the Alps themselves. However, one could argue that the case of Intona is different by virtue of the fact that it proposes a sui generis model of art that differs from a painting or a musical composition. In this sense, we might say that for Raaymakers “the model is the message”. Moreover, the richness of Strauss’ musical expression within the symphonic poem medium makes it appear self-sufficient by providing a saturated experience, whereas the deliberate sonic poverty of the conceptual work demands complementary forces of discourse when judging its æsthetic experience. Perhaps this can be mapped to McLuhan’s distinction between “hot” and “cold” media. The model of art proposed by Raaymakers in his work implies a discourse that is embedded in its medial configuration and is not external to it by virtue of the work’s minimal execution. In the conclusion of the Destructive Character, Raaymakers offers another formulation of what we have just discussed:

High “masterly” art is too layered and too complicated, and therefore not modelled enough, to be able meaningfully to interact with a world which qua [sic] complexity is fit together at least as “highly” and “masterfully” as art. If a mutual, interactive correspondence between two opposite members is to be meaningful, such a connection requires on both sides factors that are related, and can therefore be exchanged. Those factors have to be simple, univocal, thus operable before anything else. Without them, no real communication can happen between both members; maybe some specimens of more or less vague induction, but no communication on the level of language and speech. And, in spite of the “destructive character” of the destructivists, the latter is what they wished to strive for in the end: making their ideas and views communicable on the level of speech, so as to be able to influence the other parties involved. 8[8. Interestingly, these ideas are very similar to those of Lehmann as the notion of model necessarily implies a certain isomorphism.] (Raaymakers 2011, 85)

It will be argued below that the model Intona proposes is inextricably linked to Raaymakers’ explicit discourse. Prior to doing so, however, we should explore in more detail the issue of participation he has raised.

The Spectator-Amateur and the Spectator-Consumer

Intona proposes a model of art and art-making that is a special form of play, separated from reality, whose forms of presentation provide a means by which to contemplate it. As an exemplification of the reductionist isomorphism proper to conceptual works, it implies a contemplation that is at once discursive and sensory.

Wittgenstein’s discussion of the multifarious “family resemblances” between different types of games articulates a variety of manners of their participation. Indeed, one can play alone or in teams, with or without spectators, as an amateur or professional. However, the “high arts” that interest McLuhan in his theory, the ones through which “society speaks to itself,” are mass media (McLuhan 1994, 245) — which requires an audience.

Indeed, the same observation can be found in an earlier remark by Marcel Duchamp about his readymades. The core essence of these works consists in little more than the “anæsthetized” and subjective decision of an artist who would arbitrarily decide whether a specific everyday item is to be considered art or not, thereby reducing the expressive act to absurdity. The readymades of Duchamp and other artists amounted to an ostensible and historical refusal of “high art”. In the extremely subjective practice in which these works were conceived, the artist’s function and role have in some way been reduced to being a specialized form of “beholder”. However, subsequently these objects were not only numbered and signed by the artist, but became part of the very realm of high art they were meant to criticize, and consequently surrendered, in spite of Duchamp, to the art world’s commercial model:

I’m sorry about it. But at the same time if I hadn’t done it, I would have completely been not even noticed…. You’re right, there are probably a hundred people like that who have given up art and condemned it, and proved to themselves that it wasn’t necessary, like religion, and so forth. And who cares for them? Nobody. (Duchamp cited in Lazzarato 2014, 33)

Thus, even in one of the most radical refusals of Western art history, one of the fundamental and defining characteristics of artwork has been preserved: the incontrovertible difference between art and life — not to mention the separation between the artist and the spectator. Art needs witnesses who, as third parties, believe in the works and enable their existence. McLuhan provides an alternative formulation of this principle when he says that “in a native society there is no true art because everybody is engaged in making art” (McLuhan 1994, 240).

The core of the participative structure of western art may be considered thus: the specialized artist presents different forms of content, which have been “encoded” in one or more media, to a non-specialist public that is expected to have the means and ability to comprehend them.

Put in these terms, the distinction may seem excessively restrictive and prescriptive. However, it is important to bear in mind that there is a certain fluidity between the specialist and the non-specialist. There is not, on one side, the absolute specialist, the only one capable of making art, and on the other, the complete non-specialist passively absorbing the proposed information. The notion of the amateur is key here. Indeed, within the European classical music tradition, for example, an abundance of music has been written for amateurs of various levels. Also, the practice of the piano reduction was intended to enable orchestral works to be heard in private contexts. Mediation between the composer and the audience is therefore neither originally nor necessarily a matter of the pure activity of the former versus the pure passivity of the latter despite the fact that this seems superficially to be the case in the concert situation. Historically, a common way of experiencing art was in fact to practise it oneself as an amateur (Fig. 9). 9[9. Of course, the constitution of the modern public is a vast and complex subject, and this is only a schematic outline of it to facilitate the present discussion.]

The term “amateur” can be understood in three different ways: as an emotional disposition, as a practice and as a social status. The Latin amātor (from which the French term is derived) refers to someone who shows a predilection for, or loves, something or someone, doing so “as an amateur: voluntarily, graciously, for pleasure and as otium, that is to say as leisure — which means… as freedom” (Stiegler 2008, 186). And it is in this sense that they are fundamentally non-professional.

“Amateur” is the name given to those who love works of art or who realize themselves through them. There are amateurs of science and technology just as there are amateurs of art. The figure of the amateur extends the concept of taste such as it was understood during the Enlightenment, as an intelligence of sensitivity or a mediation of the now, as a singular yet educated sentiment. It thus accompanies the question of cultivating a critical public (irreducible to the “audience” — in the sense of ratings). (Petit 2013 [our translation])

The amateur therefore possesses knowledge of the practice of professional artists that allows them to be critical, to exercise their taste.

From this perspective, the distinction between the amateur and the artist can be made according to their level of specialization and expertise but is also informed by the Aristotelian opposition between “potentiality” and “actuality.” There is, however, a continuum of sorts between the amateur and the artist in the sense that the latter has origins as the former, and has gone through a transition from being able to appreciate artistic works to being able to actually realize them. Said sub specie ludi, the person who participates in the game as a spectator is the one who is involved in the game cognitively, even corporally and thus could imagine replacing the player in the act. In this sense, there is knowledge of not only what the actions in the game are, but also why they are performed. 10[10. It could, however, be argued that there exists a form of “æsthetic experience” that does not necessarily require comprehension of the “rules” of Art but could nevertheless succeed in affecting and moving the “soul” of the beholder. The mere æsthetic experience without an understanding of these rules is quite the opposite to a po(i)etic awareness of the modalities of creation specific to artistic and artisanal technique. It could then be that such an “uninformed” æsthetic experience precludes to a large extent the possibility of an adequate artistic communication between the creator and the spectator. This is maybe what Raaymakers is referring to when he speaks of a “more or less vague induction”.] This seems quite explanatory in the case of sports fans, for example.

However, amateurship as we have just described it underwent a transformation at the time of the Industrial Revolution that philosopher Bernard Stiegler has defined as the “machinic turn of sensibility”.

[T]he development of cultural industries leads to a proletarianization of sensibility on the part of the consumer via the apparatus used to channel and reproduction of perception — just as industrial machinism has made the proletarianization of the producers possible. By “proletarianization,” I mean here the loss of knowledge. […]

Throughout the entirety of the 20th century, the development of… machinic reproducibility has led to a generalized regression of psychomotor knowledge that was previously the domain of the art amateur. … Having lost this knowledge, the amateur becomes a cultural consumer. (Stiegler 2016, 75–76)

This proletarianization of the amateur gradually transforms an active amateur public into a passive consumer audience in the interest of cultural industries whose goal is to accumulate capital.

A public adopts, appropriates the artwork [and] is nourished by its criticism, whereas the audience adapts the availability of our minds, uses our attention for consumption, and decomposes us into profiles, samples, targets and masses. There is no public that is not critical, and there is no criticism without profound attention, that which is liquidated by ratings strategies that strive to increase the number of heads available for advertising. (Petit 2013)

In sum, the mediation that once existed between the amateur and artworks has been modified by technologies that can reproduce them automatically.

Some remarkable insight into this process has been expressed by the composer Béla Bartók, who provides a kind of indirect testimony to the transition. In his lecture “La musique mécanique,” he reviews the advantages and disadvantages of this “machinization” of sensitivity. He goes on to give directives concerning the “healthy” use of the radio, which is:

For those who regularly attend concerts, for those who refuse to renounce active musical practice, for those who are aware of the deficiencies of radio broadcasting, for those who possibly compensate for them by reading — at the same time as they listen — to the score of the work being broadcast…. (Bartók 2006, 245 [our translation])

These healthy practices are opposed to the detrimental use of the radio as a means to “go about your business with less boredom” (Bartók 2006, 245). Bartók also formulates a rather pessimistic assessment of the future of music, which will be in competition with its own simulacrum.

We can assume that average listeners of radiophonic music will become so accustomed to distorted timbres that they will gradually become insensitive to the vitality of sonic colours; or even that, having become so accustomed to the colour of the artificial, they will no longer be able to appreciate natural music. (Bartók 2006, 245)

This opposition and criticism are reflected in Intona’s “explicit message” according to Mulder and Brouwer:

Since the sound no longer has a substantial quality, it can be multiplied and distributed all over the world through phonograph records, radio transmitters and such. The trade in this “product” is called the “music industry,” and it has its downside. According to Raaymakers, the presence of microphones in our society has caused an excess of passively reproduced sound and a dearth of autonomous music composed and produced using electronic means. The latter is authentic, rather than being a slavish rendering of primary music. (Brouwer and Mulder 2009)

It is worth noting that this destructive critique of a passive sensibility is another important convergence between Raaymakers and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who asserted in the first Manifesto of Futurism that:

To admire an old painting is the same as pouring our sensibility into a funerary urn, instead of casting it forward into the distance in violent spurts of creation and action.

Do you wish to waste your best strength in this eternal and useless admiration of the past, an activity that will only leave you fatally spent, diminished, crushed? (Marinetti, cited in Rainey, Poggi and Wittman 2009, 52)

We can make it even clearer in the musical domain by returning to Russolo. The theory of the noise-sound of the Futurists is also inscribed in a genealogy of machinic sensibility. Indeed, we can read in the Art of Noises:

At first the art of music sought and achieved purity, limpidity, and sweetness of sound; later it incorporated more diverse sounds, though it still took care to caress the ear with gentle harmonies. Today, growing ever more complicated, it is seeking those combinations of sounds that fall most dissonantly, strangely, and harshly on the ear. We are drawing ever closer to noise-sound.

This evolution of music is parallel to the multiplication of machines, which everywhere are collaborating with man. Not only amid the clamor of the metropolis, but also in the countryside, which until yesterday was normally silent, in our time the machine has created such a variety and such combinations of noises that pure sound, in its slightness and monotony, no longer arouses any feeling. (Russolo, cited in Rainey, Poggi and Wittman 2009, 134)

The main target of Russolo’s criticism is the symphony orchestra, understood as the main medium of “high art” in which they operate and at the same time from which they try to detach themselves.

Is anything more ridiculous than the sight of twenty men furiously bent on redoubling the meowing of a violin? Naturally all this will… disturb the somnolent atmosphere of our concert-halls. But let us go together, as Futurists, into one of these hospitals for anaemic sounds. Listen to it: the first bar wafts to your ear the boredom of the already-heard and gives you a foretaste of the boredom to follow in the next. (Russolo, cited in Rainey, Poggi and Wittman 2009, 135)

The creation of the Intonarumori is then the direct consequence of this logic. New instruments must be created in order for music to remain relevant to and adequate for the modern world. It is through this liberation of sound — turned “sound-noise” — that will take place the violent and rapid anthropological revolution that the Futurists anticipate will arise.

It could be said that Raaymakers’ work also deals with an increasingly hegemonic and omnipresent mediation technology: the microphone. However, the direction of his approach is different. It is the content that must be adapted, because the passivity of the audience is facilitated by virtue of the very mediation of the music. In this sense, Raaymakers’ project is perhaps closely aligned to and offers a solution to Bartók’s observations. A music passing through fewer intermediaries would then be less likely to proletarianize the public and help them avoid becoming an audience. The basic idea is rather simplistic, but the way Raaymakers responds to it produces an interesting configuration that certainly merits further exploration and development. The solution of literally “short-circuiting” the passively mediated is to exploit the artificial organs as instruments: “Intona’s intention is to discover what the microphone thinks about [its role in the change from produced to reproduced sound], and whether it has its own voice and can speak, sing, play and communicate without waiting for our permission first” (Brouwer and Mulder 2009). As we shall see, this gesture is also charged with political intent.

Dis-closing Closed Devices

In Destructive Character, Raaymakers describes the construction of a “technical apparatus, a tool, a machine, gear, equipment and of course an instrument” (Raaymakers 2011, 26) as a typical example of a closed form of order. The inner functioning order of the construction is covered by an “instrumental appearance” that the builder, a highly specialized professional, has devised so that it may be used by less specialized third parties as an interface.

We can recognize this idea in familiar cases of industrially manufactured reproduction technologies and the restriction of their affordances that result from the process. While their use may have in fact been greatly facilitated by their enclosure, the producers of these technologies have effectively hidden their functioning in favour of their functionality. The devices become more and more technically sophisticated while being ever easier to use. Moreover, the maintenance and repair of these objects are almost entirely regulated and managed by their manufacturers — indeed the end user is not even supposed to “open” the device. 11[11. This can be related to remarks by French philosopher Gilbert Simondon (who had an important influence on Bernard Stiegler) about “reticular objects” and more generally about the “technical mentality”. See, for example, Arne De Boever, Shirley S.Y. Murray and Jon Roffe (Eds.), Gilbert Simondon: Being and technology (Edinburgh University Press, 2012).] In this sense, there is a loss of knowledge, a “proletarianization” — in Stiegler’s sense of the user — that Raaymakers finds to be “particularly expressed in the inability of the average citizen effectively to disassemble technical constructions.” He adds that this “average citizen” is in general “hardly interested in any insight into the disassembly of his recently acquired piece of technique.” (Raaymakers 2011, 40) The proletarianized user has no choice but to use the device according to a strict “programme” to keep it running, because

the opening of a closed order is exclusively reserved for “the designated person”. The best person imaginable is of course the one who previously closed what has been ordered and completed, the arranger that is. Or else it can also be someone who in his turn is appointed by the arranger: a sort of professional opener, literally a dis-mantler. (Raaymakers 2011, 25)

At the complete opposite of this professional is the completely proletarianized layperson. Should the latter develop a desire for more knowledge than what the interface allows or reveals, there would seem to be no other choice than to destroy the device to open it.

The absolute antipode of cautiously opening something which has been carefully closed is violently breaking it open. There are two properties characterizing the use of violence. The first one is that the opening is effected with literally one blow. The second one is that this blow is dealt by third parties — bystanders, let alone “burglars”. (Raaymakers 2011, 25)

With these remarks, we can finally begin to articulate something of the symbolic meaning of the destruction of microphones in Intona. The work is a model of reality in which the logic of the proletarianization of the amateur is taken to its logical extreme. Raaymakers represents the absolutely alienated amateur on stage, who has only violence as a means of reclaiming the art through which he wants to realize himself. The microphone, a vector of proletarianization that creates a form of passivity in the listener (who has become a pure consumer), can only be destroyed by the person who wants to open it and play actively with it (Fig. 10). Playing here means treating the microphone as an instrument. The microphone is thus emancipated from its role as a “slavish renderer of primary music.” Paradoxically, the effect of this destruction is ultimately a new intimacy between the destroyer and the device, as a kind of primordial form of care 12[12. In the same way perhaps that the autopsy is the first step towards the operation in the field of medicine.] practised by most instrumentalists towards their musical instruments. In the end, this liberation is as much that of the microphone itself as that of its user.

This is done through a game which, as we have said, considers the apparatus as a form of instrument. However, if in order to make art one can play an instrument or play with an instrument, Raaymakers seems to show that one can also make art by playing “against” the devices as restrictive reproduction tools. One could go even further and suggest that it is the art of playing against them that leads to a real kind of freedom and is able to assume deeper and more political meaning than playing as seen in Huizinga’s theory for example, where it is mainly used to describe an unconstrained and enjoyable action.

Freedom Through Apparatuses

It is with such a thesis that Vilém Flusser, in his essay Towards a Philosophy of Photography, presents a model for a theory of photographic art that, adapted to microphone-based art, is of interest to our discussion. It offers some perspectives that can help us to understand more precisely how such art functions and in what way it implies “true” freedom.

Flusser defines the apparatus in a way that is doubly relevant here. He inscribes it, on the one hand, in the ludic sphere and, on the other, in the genealogy of the machinic sensibility that we have previously discussed:

Apparatuses are black boxes that simulate thinking in the sense of a combinatory game using number-like symbols; at the same time, they mechanize this thinking in such a way that, in future, human beings will become less and less competent to deal with it and have to rely more and more on apparatuses. Apparatuses are scientific black boxes that carry out this type of thinking better than human beings because they are better at playing (more quickly and with fewer errors) with number-like symbols. Even apparatuses that are not fully automated (those that need human beings as players and functionaries) play and function better than the human beings that operate them. (Flusser 2006, 32)

The definition of “game” that Flusser gives here is much more specific than the one we proposed earlier. Indeed, the “programme” of the device is for him a game, in the sense of a combinatorial domain consisting of a finite number of parameters. As these parameters are defined in the “black box” — the closed construction accessible by the interface — the number of “authorized moves” that can be made by the user is limited in a certain way. This means that the programme of the device contains as potentialities only all the actions it has been programmed to afford and, foreseeably, all the combinations thereof.

Flusser’s idea is, in short, that the combinatorial game of the apparatus’ programme plays itself out. The subjects who use it “correctly” are therefore “functionaries” whose illusory freedom is in fact programmed in advance by the apparatus — they are more played by the apparatus than the inverse. In other words: “In the act of photography the camera does the will of the photographer but the photographer has to will what the camera can do.” (Flusser 2006, 35)

Although the photographic universe can be expanded almost indefinitely, the information presented by images, which will inevitably be found to correspond to various categories, are at risk of becoming redundant due to their predictability. The “true” photography is for Flusser the one that produces relevant information in the cybernetic sense of the term, namely improbability. 13[13. He seems to define information as a differing of entropy: “Pieces of information are improbable states that break away again and again from the tendency to become probable only to sink back into it again and again.” (Flusser 2006, 77)] This then constitutes a free action because it is not programmed:

First, one can outwit the camera’s rigidity. Second, one can smuggle human intentions into its program that are not predicted by it. Third, one can force the camera to create the unpredictable, the improbable, the informative. Fourth, one can show contempt for the camera and its creations and turn one’s interest away from the thing in general in order to concentrate on information. … Freedom is playing against the [devices]. (Flusser 2006, 80) 14[14. The original German version uses the word “Apparat”. I have adapted the translation because “device” seems to be more appropriate than “camera” in this context.]

At the level of the spectator, the goal of “true photography” holds ethical significance: it is necessary to expose the illusory nature of technical reproductions:

[A] lack of criticism of technical images is potentially dangerous… for the reason that the “objectivity” of technical images is an illusion. For they are… not only symbolic but represent even more abstract complexes of symbols than traditional images. They are metacodes of texts which, as is yet to be shown, signify texts, not the world out there. (Flusser 2006, 15)

The philosophy of photography, or mutatis mutandis of any art that is produced by technical means, not only deals with machinic art, but also seeks to “address the question of freedom in the context of apparatus in general.” (Flusser 2006, 81.) We can then measure to what extent such a practice is relevant by considering the definition of the term proposed by Giorgio Agamben:

I shall call an apparatus literally anything that has in some way the capacity to capture, orient, determine, intercept, model, control, or secure the gestures, behaviors, opinions, or discourses of living beings. Not only, therefore, prisons, madhouses, the panopticon, schools, confession, factories, disciplines, juridical measures, and so forth (whose connection with power is in a certain sense evident), but also the pen, writing, literature, philosophy, agriculture, cigarettes, navigation, computers, cellular telephones and — why not — language itself, which is perhaps the most ancient of apparatuses…. (Agamben 2009, 14)

Playing against the apparatuses is then not only a political gesture but also a way to show (and not only verbalize) their mediality, thus revealing their illusory nature (Fig. 11). The realization of conceptual artworks involving apparatuses, as minimal as their use may be, differs then greatly from a mere discourse. One could say that Raaymakers’ work (among many others) functions perceptually as a “negative media theory”.

We have explored here how certain forms of art could imply theory in the sense of conceptual knowledge. Dieter Mersch, to whom we owe the expression “negative media theory”, helps us in an interesting way to conclude this text by pursuing the comprehension of art as theory. By returning to the etymological roots of the term, he advances that the multiple meanings of the Greek term “theôría” are not only bound to perception (notably the visual), to the “wide horizon of art and that of sight or insight,” but also “to the realm of theater, public festivities and rituals.” (Mersch 2019, 223) [We might, in passing, note the proximity with the ludic sphere.] In short, art in general would then be a “form of thought belonging to the θεωρία (theôría) in the broadest sense” (Ibid.). When considering art as a theory, however, it is not really a question of what art knows specifically, but how it knows it. For Mesch, art is a mode of knowledge, a perspective on things operating through their “showing” (which in no way necessarily excludes conceptual works). In the case of artistic practices such as the one proposed by Raaymakers, the “percepts” are then themselves theoretical by virtue not only in terms of the representations (discourse) that are attached to them but also in their very presentation (artistic medium). In other words, in such cases as Intona, dealing with the mediality of apparatuses cannot be done fully through an additional textual mediation but needs to be immanent to the very medium it tries to investigate. A negative theory of media is thus defined

not so much by its axioms as by its mode of operation, which dwells only in negative practices: interventions, deregulations, obliterations, obstructions, deletions and other similar stratagems. These practices are negative only insofar as they produce deviations; they are therefore in each instance differential strategies. As a “non-determinable concept”, the mediality can only be apprehended in an immanent manner, through an open and always precarious process, in which, as with the image of a prism of glass, every displacement causes novel facets and aspects to glimmer. (Mersch 2018, 270)

Concluding Remarks

We have addressed a number of topics here that at times might have seemed quite disparate. Before bringing the discussion to a close, it could be useful to gather and reorganize these scattered points in order to provide a more synthetic perspective on what has been said. Generally speaking, the goal has been to explore the possibility of analyzing a particular conceptual piece by trying to develop a theory of and through art that could be seen as arising out of it. Clearly, this was a speculative exercise of interpretation based on Dick Raaymakers’ artworks as well as his and others’ writings. However, particular attention has been paid to staying as close to and as compatible as possible with his ideas while attempting to expand on them when necessary.

Intona exemplifies a theory of art as a form of play whose participation is structured in a specific way. This participation involves an amateur actually or potentially and imaginatively engaged in the practice of play. The amateur’s ability to play and their sensibility are in an interdependent relationship. This sensibility has changed over the course of history, notably because of the development of reproduction media, and therefore one no longer engages in the same kinds of “art-games”, or in the same way, as before. The development of artificial perceptive organs has thus deeply transformed the way of practising and conceiving art, causing the appearance of new medial configurations of which a verbally expressible content has become a fundamental aspect. In fact, faced with the impossibility of communicating through forms of play whose rules we no longer understand as a civilization, the solution of some specialist artists to guarantee communication with any proletarianized amateur has been to make art pass through language. Language, which can be considered as the basis of any civilization, becomes the irreducible contemporary foundation of the understanding of art. The work, based in language, is then a verbal model of reality that is simplified to such an extreme that communication can occur. 15[15. Of course, this should not be considered as a complete genealogy of concept art.] Thus, Intona as a conceptual work, tries to propose a game whose functioning, simplified as far as possible, is ultimately comprehensible to the music consumer (as opposed to the amateur), who would have lost all engagement with “real” music.

Raaymakers, as a performer, provides a model in two ways. He is involved in a reduced representation of reality that allows for reflection. Further, he represents the public that has become an audience whose only possibility to reappropriate the devices is to play against them in order to exercise through them an unprogrammed freedom. He can also be seen as a model by virtue of the participatory structure of Art that the work implies (Fig. 12). There is no fundamental difference between Raaymakers (at the time of the performance) and any member of the audience. The concept could potentially be convincingly realized and understood by anyone who has a command of language. The artist is just another amateur-in-the-making, who by example tries to persuade the passive audience to become an active public again. In this, Raaymakers demonstrates a barely concealed didacticism. This does not mean, however, that the work would be better or more complete if the public helped him to destroy the microphones. Actually acting out is not necessary to be an active spectator.

In Intona, we also saw an ambivalent reference to the Futurists. On the one hand, they share themes and postures that could be summarized as follows: they criticize — destructively — the hegemonic media that cause sensibility to become passive. On the other hand, they are actually completely different: we see the difference between the avant-garde, full of hopes for an art that would transform the world in a direct and palpable way, and the artists more or less 80 years later who believe in an indirect power of art but use other strategies to act on reality. This does not mean that they no longer hope for art to impact the real world:

[A]ccording to my own conviction, the theme of “destruction and art” is art historically speaking completely out of fashion, it is however in a social and political sense more present than ever, especially when considering the increase in destructive violence and all those horrible attacks and social disintegration around us. (Raaymakers 2011, 6)

Of course, Raaymakers’ “conclusions” are a bit dated. To continue this text would surely lead to the question of the renewal of the amateur with the extreme democratization of personal computers and of all kinds of programmes that allow users, for example, to reappropriate the profusion of content available on the Internet. This has led, at the very least, to a quantitative increase in electronic music and musicians. Stiegler himself speaks of a “second machinic turn of sensibility.” In this sense, we can perhaps say that Raaymakers was in part a visionary when he dealt with this question thirty years ago. The new situation then implies new negative theories of media, that remain to be invented.

Bibliography

Adorno, Theodor W. Æsthetic Theory. Trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor. London-New York: Continuum, 2002. http://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctv125jvbt

Agamben, Giorgio. “What is an Apparatus?” and Other Essays Trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press, 2009. http://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=17450

Bartók, Béla. “La musique mécanique.” In Béla Bartók: Écrits. 1st Edition. Edited by Philippe Albèra and Peter Szendy. Geneva: Contrechamps, 2006. http://doi.org/10.4000/books.contrechamps.1392

Brouwer, Joke and Arjen Mulder (Eds.). Dick Raaymakers: A Monograph. Rotterdam: V2_Publishing, 2009. http://v2.nl/publishing/dick-raaymakers-a-monograph

Flusser, Vilém. Towards a Philosophy of Photography. Trans. Anthony Mathews. London: Reaktion Books, 2006.

Huizinga, Johan. Homo Ludens: A Study of the play element in culture. Boston MA: The Beacon Press, 1964.

Kosuth, Joseph. “Art After Philosophy.” 1969. UbuWeb. http://www.ubu.com/papers/kosuth_philosophy.html Originally published in Studio International 178/915 (October 1969), pp. 134–137. http://archive.studiointernational.com/SI1969/october/vol178-no915.html#p=134

Kreidler, Johannes. Sätze über musikalische Konzeptkunst: Texte 2012–2018. Hofheim am Taunus: Wolke, 2018.

Lazzarato, Maurizio. Marcel Duchamp and the Refusal of Work. Trans. Joshua David Jordan. Los Angeles CA: Semiotext(e), 2014.

Lehmann, Harry. “Conceptual Art and Conceptual Music — A Model of Conceptualism.” Keynote Lecture, International Graduate Centre for the Study of Culture (GCSC), Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen (Germany), 11 December 2018. YouTube video (59:00) posted by “Harry Lehmann” on 6 April 2019. http://youtu.be/F7EGpa2hDmQ [Accessed 1 August 2022]

LeWitt, Sol. “Sentences on Conceptual Art.” 1968. UbuWeb. Originally published in Art-Language 1/1 (May 1969). Available at http://www.ubu.com/papers/LeWitt_sentences.html

Lista, Giovanni. Le Futurisme: Textes et manifestes (1909–1944). Ceyzérieu: Champ Vallon, 2015.

Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA). “Sol LeWitt: A Wall drawing retrospective.” 2008 [?]. http://massmoca.org/event/sol-lewitt-a-wall-drawing-retrospective

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The extensions of man. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 1994.

Mersch, Dieter. Théorie des médias: Une introduction. Trans: Stephanie Bauman, Philippe Farah and Emmanuel Alloa. Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2018.

_____. “Art as theoria (θεωρία).” In Æsthetic Theory. Edited by Dieter Mersch, Sylvia Sasse and Sandro Zanetti. Zürich: Diaphanes, 2019.

Petit, Victor. “Vocabulaire.” Ars Industrialis. http://arsindustrialis.org/vocabulaire