The Musical Underground and the Popular and Classical Overground

Why classify? A lot of my scholarly life is taken up with this question. As aware as I am of the disciplining, institutionalising force of the kind of musicology and music writing that tries to gather, delimit and name, I’m also irresistibly drawn to organising music and its cultures in this way. It’s probably an artefact of my training. As a student, I was taught to experience musical history as a series of practices and work-objects classified historically, stylistically, nationally and, less consciously, in gendered and classed terms. Immersing myself in the verbal cultures around popular and other musics, it was “all genres and subgenres, all the time”, so to speak, with magazine articles and reviews proliferating genre names passionately, musicians coding influences explicitly and semiotically in generic terms, and technologies such as web streams using genre labels in metadata algorithms that further discipline and organise our listening. Gathering and bundling generically is key to musical discourses large and small. As Simon Frith says: “It is genre rules which determine how musical forms are taken to convey meaning and value” (Frith 1996, 95). Even as I recognise the potentially aggressive political valence of this pervasive gesture of generic organisation — as Philip Bohlman points out, musicology that seeks to discipline and organise is always acting politically (Bohlman 1993) — I can’t stop myself from doing it.

These tensions between “unmediated” music — though music is always already pre-filtered and mediated in important ways — and disciplinary organisation are key to the area of research and music I’ve spent the most time with over the past ten years or so, the “underground” music of my title. In existing either outside or on the fringes of mainstream musical institutions such as the commercial marketplace and the subsidised / supported high art nexus, this music falls between the classificatory cracks. Neither high nor low, classical nor popular, the music occupies an as yet unsettled territory. Various organising terms are bandied about within the discourses around this music to tie it together in some loose way, from “underground” to “experimental” to “outsider” to “marginal” to “fringe”. But none of these has gained traction as a catch-all term that might do the same (problematic, but decisive) work as discourse setting terms such as “classical” or “popular”.

Without wanting to police this territory autocratically, without wanting to impose one organising term and in this imposition push out things that don’t fit, and remould things that might, I would put forward the terms “underground” and “fringe” as useful guiding metaphors. They operate in my work in a loose, open, non-determinative way that yet functions to bundle and thus illuminate a broad range of connected practices. Even here I’m fighting against the fear that this gesture of organisation does some kind of violence to the music. And yet my hunch has been that, given as a set of catalysing questions and answers not as one monolithic “answer”, as one possible map among many (the map is never the territory after all), research that shows the sympathies that configure these cultures together as a possible alternative or supplement to the high / low spectrum that still pervades music culture, as a “fourth way” beyond Philip Tagg’s “axiomatic triangle” of folk, art and popular musics (1982), will ultimately do more good than harm as an explanatory and illuminating force.

In the next section I discuss the character and contexts of the underground and its fringe as a way of fleshing out my case in a little more detail. I draw in doing so on certain passages in the first chapter of my book on the subject, Mapping the Underground, to which readers are referred for a much fuller explanation and exploration of these issues. I then move on in the third section to float the notion, tentatively, that this experimental “underground” and popular and experimental “fringe” might potentially be seen as a spectral pre-figuration of “high” culture to come in the post-social democratic, post-social contract, neoliberal West.

What Is the Underground, and How Does It Relate To “High” And “Low” Culture?

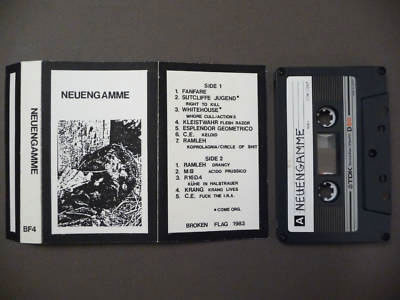

There are various ways to describe the range of practices I refer to in using the terms “underground” and “fringe”. One would be to point to the messy cluster of avant-gardish music scenes that have developed outside or tangential to mainstream culture(s) over the past forty to fifty years, chiefly in Western Europe and America but also in locations such as Japan, China and Eastern Europe. 1[1. The term “avant-gardish” isn’t found in my book, but Chapter One nevertheless explores the “avant” nature of these musics.] These would include genres such as death ambient, free improv, wall noise, power electronics, DIY, extreme metal forms and more. Noise and industrial artists such as The New Blockaders, Skin Graft and Severed Heads, extreme metal acts such as Xasthur and Lord Foul, and DIY and improv groups such as Morphogenesis and the Los Angeles Free Music Society all made and make music and occupy a cultural position that would place them somewhere in the dynamic spectrum of underground music, which doesn’t quite fit in either the high art tradition or that of popular culture. Other acts would fit into what I call the fringe. This would include on the one hand cult experimental metal groups such as Sunn O)) or Agalloch, “popular” noise bands like Wolf Eyes or Melt Banana, industrialists such as Throbbing Gristle and SPK, and experimental electronic artists such as Gas or alva noto. The fringe would also include, on the other hand, improv-composers such as Skogen, Polwechsel, Konzert Minimal and Group Ongaku and noisy sound artists such as Ryo Ikeshiro or Florian Hecker. These artists fringe both the underground and a mainstream, in the first case the latter being represented by more commercial contexts, and in the second by more conventional “high” art traditions.

This, in brief, is how I understand my terms “underground” and “fringe” to be operating: the first as a descriptor of properly marginal, generally radical æsthetic and political practices, and the second of slightly more commercial or slightly more traditionally high cultural, but nevertheless fairly marginal and exploratory, practices. 2[2. For overviews and analysis of some strains within the “underground” see P. Hegarty’s Noise Music: A History (2007) and D. Novak’s Japanoise: Music at the edge of circulation (2013). As noted, readers should also look for a fuller account of these and many other relevant issues to my own book, Mapping the Underground, in which I draw on themed narrative interviews with practitioners and on critical analysis of a variety of “texts” in building up a wide ranging “map” of the underground.]

Considering the liminality represented by the range of examples just given as illustration of the size and shape of the underground and its fringes, which range spreads across categories both horizontally and vertically (taking influences from up and down the cultural spectrum), it would be easy to suggest that these underground and fringe musics result from a sort of dialectical synthesis of tendencies from “art” music (silence and noise, improvisation, dissonance and free meter, conceptualisation) and popular music (guitars, distortion, playing in clubs and so on). This synthesis would be daubed with a dose of radical political separatism coming from two directions likewise, from countercultural practice in popular culture and from avant-garde political theory in the academy. But this would be to settle difficult territory in too smooth a manner. So I won’t do that. I would though point to the fact that this music isn’t clearly classically high art nor popular low culture in its institutions, contexts or sounds, and so in some senses at least can be described as a kind of messy, “nobrow”-like confusion of these “high” and “low” tendencies. 3[3. For more on nobrow in a more general context see J. Seabrook’s “Nobrow Culture: Why it’s become so hard to know what you like” (1999).] It would be a mistake though to see this description as prescriptive or to set these cultural categories in a rigorously causal and hierarchized relationship; the underground should not necessarily be seen as a derivation of art and popular musics, but as a parallel set of practices operating within the same converging cultural and social tendencies that have shaped those practices likewise.

Another way to get a sense of what I mean by “underground music” and “fringe music” is to look at an example of a typical practitioner and their work, even very briefly 4[4. In addition to the present article, Mapping the Underground includes a variety of case studies of musicians, labels, festivals, organisations and so on operating within the underground.], and in so doing get a sense of the language, attitude, contexts and repertoires in play in the underground and its fringes.

Rob Hayler runs the blog and review site Radio Free Midwich. He is a noise musician (operating as “midwich”) based in the UK, a country with a proud noise tradition that extends back to Whitehouse and Broken Flag and others in the 1970s and 1980s, and runs right up to labels such as Sacred Tapes, musicians such as Richard Youngs and organisations such as Cold Spring today. Hayler ran his own “micro-label” (comparable to the self-producing and self-distributing labels discussed by Robert Strachan, 2007), fencing flatworm recordings, in the 2000s. He also used to co-curate an experimental music club night at the Adelphi Hotel in Leeds, Termite Club, which had been originally set up in the early 1980s by Alan Wilkinson. 5[5. P. Coward and S. Cooke’s “Thoughts on Fencing Flatworm Recordings, oTo, Rob Hayler, midwich and radiofreemidwich” (2014) offers an overview of the label and of Hayler’s general activities in a journalistic context.]

Hayler and his colleagues write extensively about what he calls the “no-audience underground”, a territory very similar to the one I’m discussing in this article and which I formalise loosely in Mapping the Underground:

Comrades… When I started Radio Free Midwich at the end of 2009 I claimed its function to be as follows: “During the first five years or so of this century I created music (mainly) under the name midwich, released music on the micro-label fencing flatworm recordings which I co-ran with my colleague Sean Keeble, and helped run the Leeds experimental-music institution Termite Club. Now in my twilight years I think that this work might be fruitfully documented and made freely available to the world at large. Over the coming whenever I will be uploading documents, mp3s, photos, gig mementos and the like to create a small but perfectly formed archive celebrating my corner of the experimental, drone, electronica, free music, CD-R underground and its various no-audience-attracting projects.” (Hayler 2014)

So Hayler is musician, label head, promoter and writer, a collapsing of roles typical of the participatory, tiny underground, as seen in the multiform activities of figures as various as Wolf Eyes and American Tapes’ John Olson, Chocolate Monk label head and musician Dylan Nyoukis, and musicians, label heads and writers Amanda and Britt Brown. As a writer, Hayler reviews tiny small-run releases on labels such as Deserted Village and on media such as CD-R and tape, and writes about long-out-of-date zines, venues and nights, paraphernalia, micro-labels, internet radio stations, podcasts and so on. He is part of various intimate, internet-based communities of blogs, forums, labels and magazine sites, including in his case links with sites such as Bang the Bore and writers such as Idwal Fisher. Hayler and others like him connect to wider scene platforms and quilting points such as The Wire magazine or various zines, or a broadcasting “wing” such as WFMU radio in America (which hosts various underground and fringe-adjacent shows and figures, including those of Ergo Phizmiz and Kurt Gottschalk, whilst also obviously producing much content that transcends the underground). They also sometimes find themselves at underground shows in publicly funded arts institutions, perhaps taking part in a piecemeal subsidised tour or project, or maybe playing in a smaller space or themed evening in one of those institutions. But more often than not they make and write about music for small audiences and little financial reward in the context of nights and festivals such as the Termite Club and, beyond Leeds and Hayler, No Fun in the US, Sonic Protest in France, Arika in Scotland, and Bar Ayoama in Japan, as well as on their own sites and through their own small-run, bespoke releases.

In this way Hayler and others like him are typical of the underground music scene, which sometimes finds itself fringing large institutions or commercial appeal and sometimes reveals its close links with institutional forms such as experimental composition or sound art, but most often exists outside institutions, on the internet and in hired or tailored venues, as a tiny, hidden, obscure part of our cultural environment. Its political situation is broadly analogous to this marginalised cultural position, in many artists’ anti-capitalism and separatism that is nevertheless inflected by mainstream sympathies and participation. Even underground artists claiming an explicit political programme, from Mattin to Eddie Prévost to Whitehouse to Maggie Nicols 6[6. See Part II of my book, Mapping the Underground, for extended case studies of and interviews with artists such as Nicols, Prévost and Mattin.], like Hayler operate within and are subsumed by mainstream society up to a point.

These various artists parallel marginal venues, promoters and audiences worldwide who also operate within this distinctive non-institutional but fringing-on-the-mainstream cultural space that I call the underground, but which is also known by many other terms and is experienced and framed in many other informal and formal ways by audiences, writers, musicians and so on. My account of the underground and its fringes, given here and, most extensively, in Mapping the Underground, has simply been an attempt to offer one version or “map” of these practices. In so doing I’ve tried to show some of the ways that this music links together in operating outside or at the fringes of mainstream culture, and in emerging from Western popular and “high” cultural contexts without being reducible to or identifiable completely with either.

Conclusion: Beyond High and Low, a “Fourth” Way?

Whether the musics and artists I’ve been alluding to, alongside the many others I mean to incorporate under my underground and fringe headings, fit together smoothly is a difficult question to resolve. Some of these musics might sound rather different from each other, but even in extreme comparisons — the scrabbly noise of Skin Graft versus the ultra-refinement of improv group Graveyards, the spectral hauntology of the Caretaker versus the corrupted, wobbled pop of Gary War, the clean, refined lines of A Broken Consort versus the stogged drones of Corrupted — there is usually some pressing sense of shared modernistic critique or avant-garde estrangement relative either to parent musical genres or more generally conventional musical languages.

But correspondences in musical grammar and sound are perhaps less important in my scheme than correspondences of cultural position; all of these musics exist either outside institutions, on the fringes of those institutions or enter institutions only periodically. Along with this “petty capitalist” (see Born 2013, 64) marginality comes, in many cases, political radicalism and separatism, of left and right dispositions (left in the anti-capitalism of e.g., Mattin or the communitarianism of improv; right e.g., in the scabrous and challenging noise of acts such as Boyd Rice), which likewise draws a common thread through these musical cultures. Many of these musics, too, are written about together in magazines and sites like Sound Projector, The Wire, Signal to Noise and Weird Canada. They are played on the same shows, such as Miniature Minotaurs on WFMU, much of the Resonance FM schedule and even up to a point BBC Radio 3’s Late Junction and many other similar “polygeneric” (see Clarke 2007) or “multicanonic” (Morgan 1992) shows worldwide. They are programmed alongside each other in small festivals, from Sonic Protest in France to Supersonic in the UK, No Fun in New York, Roadburn in Holland and Kraak in Belgium. And they are heard in the same venues, from Café Oto in London to Kaija Lab in Beijing, Bar Ayoama in Tokyo and Ausland in Berlin. These musics are connected, even if they also exist within their own genre spaces and contexts.

The correspondences I’ve just drawn might be broad, but this is fitting in the context of what is after all a mapping of a very broad territory. The various threads between the musics that I’ve pointed to are not accidental or superficial — they draw these in ways disparate musics together as a global network of underground and fringe practices untied by shared æsthetic experiment, cultural marginality and political radicalism.

Postmodern, late-capitalist, post-Fordist mass production and distribution of musical commodities, lately abetted and exaggerated by digital-age overabundance and availability, has undermined these already pockmarked and permeable categories.

As will be clear by now, none of these musics fit comfortably into the current popular / classical / folk axiomatic triangle or the familiar high / low cultural spectrum, the two master frameworks of Western and Western-derived music. Noise music such as that made by Ramleh or the Haters challenges notions of the beautiful, of the performing spectacle and of what counts as “musical” sound. But even in this avant-garde politicised challenge to convention, any co-extension with tradition “high” culture is denuded by the music’s marginal position and untutored brutality. In more liminal examples from the fringe of the underground, such as, say, the abrasion-chaos of noise bands such as Ruins and Skeleton Crew or the frenzied genre and sonic collages of Naked City and Nurse With Wound, we might use familiar terms such as “rock” and “collage” in describing them, but these fall far short of the reality of these acts’ work.

So we need new terms: Classical, Popular and Folk just won’t do anymore. The political, cultural and æsthetic qualities running through all the musics discussed above push them outside the high and low, modernist and postmodernist, classical, pop and folk categories that still pigeonhole and make still musical cultures that are sprawling and many-layered. Postmodern, late-capitalist, post-Fordist mass production and distribution of musical commodities, lately abetted and exaggerated by digital-age overabundance and availability, has undermined these already pockmarked and permeable categories. In a context of a shrinking public sector in the post-social contract, neoliberal West, the notion of high and low cultures, already riven apart by postmodernism, is almost expired. The conditions that drove “high” culture — the subsidy principle of Europe and the philanthropy of the US — and even the conditions that drove experimental forms of mainstream popular musics, the “indirect social funding” of cheap rents, social welfare and free education 7[7. As discussed by M. Fisher in Ghosts of My Life (2014, 15–16).], are either dead or seem to be dying across large parts of the world. Culture is very much in flux, and it’s not yet clear in what terms the high-low relationship will settle in years to come. So I’d propose that, at the least, we supplement highs and lows with an alternative, which I’d prefer to call the underground and the fringe.

We also need to think about the future. This general cultural and political drift away from subsidised art of various kinds doesn’t mean that traditional “high” culture or vibrant popular culture will die any time soon. But I don’t think it’s ludicrous to suggest that, even if only in part, the turbulent, exploratory musical practices I’ve hinted at and tried to illuminate using the terms “underground” and “fringe” could be seen to be serving as outlets or conduits for the kinds of cultural energies formerly harnessed by public institutions and made possible by social democratic principles. The kind of exploration that used to happen within subsidised, institutional contexts — or that at least used to get quickly incorporated into those structures — now seems also to happen in these relatively new underground spaces which offshoot from both the academy and high art. It’s not as clear where the popular experimenters are going, if they have even left popular music at all, but it’s fair to see some popular energies and tools and contexts as bleeding into the underground likewise. We might be witness with these underground and fringe practices to something like a fourth way, or to something like a “nobrow” confusion of high / low tendencies, a set of affiliations and potentialities that figure extra-institutional art to come, a form of practice that fits into innovative, modernistic models, but that also moves beyond those models in existing in such marginal, self-funded, participatory cultural contexts.

The underground of which I’ve been speaking might, then, be seen as a route out of or as a useful supplement to calcified musical categories of high and low. In percolating styles and promises from across the high / low spectrum, and in participating in and reflecting the breaking apart by neoliberalism of the traditional social institutions at the heart of this spectrum, the underground and its fringes might also even be seen as the future, or the futures, of high culture. High culture is dead, long live “high” cultures, perhaps…

Bibliography

Bohlman, Philip V. “Musicology as a Political Act.” The Journal of Musicology 11/4 (Autumn 1993), pp. 411–436.

Born, Georgina. “On Music and Politics: Henry Cow, Avant-Gardism and its discontents.” In Red Strains: Music and Communism outside the Communist Bloc. Edited by Robert Adlington. Oxford University Press, 2013, pp. 55–64.

Clarke, David. “Elvis and Darmstadt, or: Twentieth-Century Music and the Politics of Cultural Pluralism.” Twentieth-Century Music 4/1 (March 2007), pp. 3–45.

Coward, Pete and Seth Cooke. “Thoughts on Fencing Flatworm Recordings, oTo, Rob Hayler, midwich and radiofreemidwich.” Available online at http://www.bangthebore.org/archives/1600 (Part 1, posted 28 September 2011) and http://www.bangthebore.org/archives/1889 (Part 2, posted 12 November 2011) [Last accessed 13 May 2014]

Graham, Stephen. “Notes from the Underground: A Cultural, political and æsthetic mapping of underground music.” Unpublished PhD thesis. Goldsmiths College, 2012.

_____. Mapping the Underground. Ann Arbor MI: Michigan University Press, forthcoming.

Fisher, Mark. Ghosts of My Life. Winchester: Zero Books, 2014.

Frith, Simon. Performing Rites: Evaluating popular music. Oxford University Press, 1996.

Hayler, Rob. “About us and this blog.” Available online on the Bang the Bore website at http://radiofreemidwich.wordpress.com/about-me-and-this-blog [Last accessed 20 May 2014]

Hegarty, Paul. Noise Music: A History. London: Continuum, 2007.

Morgan, Robert. “Rethinking Musical Culture: Canonic reformulations in a post tonal age.” In Disciplining Music: Musicology and its canons. Edited by Katherine Bergeron and Philip V. Bohlman. University of Chicago Press, 1992, pp. 44–63.

Novak, David. Japanoise: Music at the edge of circulation. Durham NC, USA: Duke University Press, 2013.

Seabrook, John. “Nobrow Culture: Why it’s become so hard to know what you like.” The New Yorker, 20 September 1999.

Strachan, Robert. “Micro-independent Record Labels in the UK: Discourse, DIY cultural production and the music industry.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 10/2 (May 2007), pp. 245–266.

Tagg, Philip. “Analysing Popular Music: Theory, method and practice.” Popular Music 2 (January 1982), pp. 37–67.

Social top