“The Thing About Listening is…”

Compositional approaches and inspiration using spoken word, field recordings and electroacoustic techniques

The Thing about listening is… was performed in the exhibition listening room at SI13. This 8-channel work combines elements of soundscape composition, electroacoustic techniques and spoken word. Here we discuss the compositional process, from the development of ideas and context to compositional techniques and performance.

The idea for this piece began in July 2012 when I attended the Global Composition Conference in Dieburg, Germany. I went on a soundwalk with Hildegard Westerkamp and came away feeling very lucky to know and understand what a soundwalk was. Andra McCartney talks about how inspiring Westerkamp was to her:

I had heard the work of hundreds of composers, and had never felt drawn to compose electroacoustic music before this. Yet now a powerful urge to record sounds and work with them on tape caused me to go out, rent equipment, and begin. Since then, I have discovered that, through her composition, teaching and radio work, Westerkamp has had a similar effect on other composers, and is a particular source of inspiration to many women composers in Canada (McCartney 1999, 10).

Westerkamp’s work is still inspiring composers like myself. As a result of this experience, I decided to organise a soundwalk in my Irish hometown, to teach people a little about soundwalking and how to listen to their environment.

The Banagher Soundwalk

A Soundwalk is any excursion whose main purpose is listening to the environment. It is exposing our ears to every sound around us no matter where we are. (Westerkamp 2007, 49)

Banagher is a small town in County Offaly in the heart of Ireland. My aim for the Banagher soundwalk was to take people into an environment that they knew and were familiar with and make them aware of the sounds within it. I took 15 people on this 50-minute walk and the age of the participants ranged from about 3 to 65 years. We met at the local library and began our journey down through the town. As we walked, we would stop at some listening points I had selected in order to listen and have a brief discussion. Usually on a soundwalk there is complete silence for the duration of the walk. However as I was talking to people who had never experienced a soundwalk before, I felt it was necessary to ease them into the walk and explain the reasons for the stops, for example to listen to birds tweeting in the tree above us or to changes in the sounds of our footsteps as we moved from concrete to gravel. This was also a great way to engage with the younger members of the group and listen to what they had to say about their surroundings.

Imagination and Soundscape

The recession in Ireland has affected our local soundscapes in many ways and this is especially noticeable in the small town of Banagher. The end of the town known as West End has very little activity due to the closure of a hotel, shops and pubs. This has a huge affect on the sounds of this area, which now seems quiet, missing the hustle and bustle of people coming and going into shops and tourists visiting the local hotel. The Shannon Hotel, which once had a healthy tourist industry, now lies derelict, vandalized and silent. The beer garden with broken wooden benches is overgrown and no longer emits chatter and music. This was one of our stopping points. I asked the group to imagine what this area would have sounded like during the busy tourist months when the Irish economy was booming. How have the sounds changed over the years? 1[1. The theme of past soundscapes and memory is explored in another composition that I completed this year, A Bit Closer to Home. The idea for this piece came about as a result of the soundwalk when a discussion took place with the participants about the soundscape of the past.] What is the impact of noise pollution on the sounds around us?

R. Murray Schafer states that noise pollution occurs when we do not listen properly and that noises are the sounds that we learn to ignore (Schafer 2004, 30). The participants considered this statement and as a group we began listening to the traffic and other mechanical sounds that we usually filter out. Some participants also discussed how natural sounds were also ignored such as birdsong, wind and the sound of the river. We also discussed how the new bypass in the town had reduced the noise pollution on the main street by taking huge lorries and trucks off the road, taking them around the town rather than through it. Due to the recession there are also fewer trucks on the road transporting goods such as sand and gravel as the construction industry has declined significantly.

Chance Encounters

The piece is structured around the conversations that I had with two natives of the town, Rosemary Porter and her brother Brian Johnson. I met Rosemary by chance in the local churchyard when I went to find the parish newsletter to see if they had advertised my soundwalk. The church was locked but Rosemary had the newsletter in her hand and I asked her if I could read it. Then a discussion began about the soundwalk, sound within the environment and my research. Rosemary is a poet and she read one of her poems in the churchyard. I instantly realized that she had a wonderful way of describing places and sounds.

Rosemary discussed the soundwalk with her brother Brian who called me and we talked on the phone about his thoughts about listening. I was invited to their house and they allowed me to record the conversation. The conversation was based around my research ideas, their thoughts on listening, the soundwalk and the poetry that Rosemary had written. The conversation was informal and relaxed and I was delighted when they gave me permission to use the conversation in my piece.

Compositional Approach in “The Thing About Listening is…”

Influence of the Soundwalk on Composition

My own practical suggestion with regard to soundscape recording and composition is to begin not with recording or processing in the studio, but rather with the experience of soundwalking in the soundscape. (Truax 2012, 4)

The very act of listening to the environment and teaching others to listen has influenced my compositional decisions in regards to choices of material and structure. Sounds that were heard and discussed on the soundwalk are represented in the piece, such as the sounds of the River Shannon, traffic and birds. The voices of participants can also be heard. The spoken word, which provides the structure for the piece, is taken from conversations that occurred as a result of the soundwalk and the interest in it that people expressed. It was wonderful to share thoughts and ideas with the community about the soundwalk and their listening experiences.

Compositional Structure

Excerpts of the recordings of my conversation with Rosemary and Brian were extracted and edited into shorter sections. Field recordings and transformed sounds are used to enhance the spoken word and reflect the content and subject matter. The piece can be divided into five sections:

Section 1: Listen (0:00–2:26)

The first part asks the listener to listen. This section is framed around the spoken word of Brian Johnson suggesting ways in which we might listen properly.

Section 2: Rosemary’s River Walk (2:16–5:44)

At 2:16 a new section begins with an introduction of a field recording taken from the banks of the River Shannon and featuring spoken word excerpts by Rosemary. This section is about Rosemary’s experience of sounds as she was walking by the river. She discusses both natural and machine sound, which are represented using field recordings and processed sounds.

Section 3: Over the Bridge (5:41–7:48)

This section of the piece explores the recordings that were made on the soundwalk as we walked across the bridge over the River Shannon. Participants were invited to make sounds with pencils and umbrellas against the railing of the bridge as we walked across, which was particularly enjoyed by the younger soundwalkers.

Section 4: The Sound of People’s Voices (7:44–10:33)

This section opens with the murmuring and whispering of voices, which introduces Rosemary’s discussion about the sounds of people’s voices, how we speak to other people and how our tone of voice may be interpreted. I had never really thought about this, as I was preoccupied with listening to the natural sounds until Rosemary mentioned this during our conversation. What she was saying about listening to people was just as important as listening to the sounds of the environment. After all, we are part of the environment and I felt it was important to include her thoughts about listening to people in the piece.

Section 5: Listening Is Just so Important (10:33–12:13)

Rosemary concludes the piece with her thoughts about listening and the impact of noise, “and the noise penetrating people’s peace and quiet and their thinking processes” (Johnson and Porter 2012). The ending of the piece allows the listener to reflect on the message and ideas within the piece structured around Rosemary’s thoughts and concerns about listening: “Value the sounds you hear, your sense of hearing. … Listening is just so important” (Ibid.).

Working with Spoken Word

Trevor Wishart discusses his interest with the voice in an interview with Cathy Lane:

It was the beginning of my discovery of the richness and complexity of everyday sounds, which forms the basis of all my later work… and the key real world sound that people relate to is the human voice. … The voice also connects with so many things. When we speak we not only convey meanings but we portray things about ourselves, simple things like what gender we are or whether we are ill or healthy, but also, perhaps, what our intentions are, what our mood is. (Lane 2008, 71)

The spoken word that provides the framework for The Thing About Listening is… has been left as natural as possible. The content of what Rosemary and Brian were saying is significant; the characteristics of their voices and manner of speaking are equally important. Even though Rosemary and Brian are brother and sister, their accents are very different, as Rose has lived in Essex for many years. Rose’s accent is strongly Irish with hints of English intonations here and there. Brian has a strong Irish Midlands accent, but softly spoken. Their accents also convey a sense of place and identity to the listener. Together they speak thoughtfully and slowly as they find the words and sentences to describe their feelings towards listening. Naturally occurring stumbles and pauses for thought, as well as their thoughts and feelings at the moment, were all captured — and preserved — in the recordings I made with Rosemary and Brian.

Transforming Spoken Word

During the compositional process I was determined to represent the excerpts of the interview in their natural state. However, as a composer I was also intrigued by the manipulation of the material and the new sounds that could be created. John Wynne discusses this dilemma:

A tension between, on the one hand, the need to respect and somehow convey the context of the recordings and the content of what is being said and on the other, the desire to explore sound itself and to express myself and the ideas and issues that interest me through work that is not purely documentary. (Wynne 2008, 79)

During the composition process I also faced this dilemma. The content and context of the spoken word are retained within the piece but I did have the creative pleasure of exploring and transforming words to create new sounds that were used in the piece.

Composers use various compositional techniques when using spoken word in their compositions. Cathy Lane has discussed these in her article, “Voices from the Past: Compositional approaches to using recorded speech” (Lane 2006, 5–7). The techniques Lane describes that apply to The Thing About Listening is… are listed below:

- Retention of meaning. Words are presented as recorded with no apparent processing.

The spoken word is left unprocessed so that the meaning of the sentences can be conveyed to the listener. The only processing involved is editing the recording into smaller pieces, equalization and noise removal. The unprocessed spoken word begins at 0:43 with Brian saying, “The thing about listening is…”

- Dissolution of semantic meaning through processing. The semantic meaning of a word or phrase is dissolved through a processing effect such as layering, overwhelming reverberation, reversed echo, spectral processing.

Examples of this type of spoken word can be heard at 0:10, 0:27 and 0:34, where spoken word is heavily processed with reverb, making the words incoherent.

- Dissolution of semantic meaning through deconstruction. Words are split into their component syllables or smaller units and are used acoustically.

Granular synthesis is used to deconstruct the words. The first instance of this technique is at 2:04 where the word “listen” is deconstructed. The first syllable “list” is distributed rapidly anti-clockwise around the circle of eight loudspeakers, repeated until 2:10 ending with the complete word “listen” at 2:11. The semantic meaning is lost as the word is deconstructed, but as the full word is revealed at 2:11 the meaning is re-established.

The word “listen” is deconstructed using BEASTtools. Within this program there is a patch called “Granul8”. The patch takes a stereo sound file and allows control of grain parameters such as position, shape and duration. The composer also has control over the pan width, which determines how many loudspeakers are used ranging from two to eight loudspeakers.

In the fourth section, “The Sounds of People’s Voices,” Soundgrain was used to generate granular synthesis materials. The word “somebody” was extracted from a sentence spoken by Rosemary in the recording and loaded into the Soundgrain software. By using this technique I was able to create various textures at different pitches that weave in and out amongst the spoken word as Rosemary is discussing “the sounds of people’s voices.”

- Narrative suggestion. Vocal events are not foregrounded but used to indicate human presence or human activity.

This can be heard at 1:08 with a snippet from the participants of the soundwalk. A young girl and a woman’s voice can be heard. At 3:32 and 3:42 we hear the young girl again on the soundwalk saying “look” when she sees a bottle floating in the water and “Oh, that was big that wave” as we were walking along by the riverside and waves from passing boats were coming to the shore.

Here the connection is made between the words of the girl on the soundwalk and the words of Rosemary in the interview. The soundwalk space and the interview space come together briefly at 3:49. At 3:35 Rosemary begins her description of the waves coming to shore as a result of boats going by: “The waves literally lashed into the reeds.” At 3:42 the young girl can be heard saying “Oh, that was big that wave” which echoes twice amongst Rosemary’s words at 3:49 as she continues, “and made this sort of swishing movement and sound altogether.”

Technology and Soundwalks: Changing the way we hear

Technology

What you see is not what you hear. When I was just listening without microphones the sound and visual matched up. … However, when I put the headphones on, the layers within the soundscape became more complex.

After the soundwalk I gathered recordings made along its route. One of the recording locations was along the banks of the River Shannon. As I looked across the Shannon everything was still and peaceful. Horses were grazing across the water in a field. Everything was still and calm despite the occasional car that passed across the bridge. My recording equipment consisted of DPA microphones taped to a drumstick, a Zoom H4n and headphones. I put on my headphones and pressed record. What you see is not what you hear. When I was just listening without microphones the sound and visual matched up. The beautiful views of the Shannon matched the sounds of birdsong, ebbing of the river and rustle of the leaves. However, when I put the headphones on, the layers within the soundscape became more complex. Suddenly I could hear further down the Shannon, the voices of people swimming and laughing upstream in the outdoor pool. As Rosemary said, “there was so much going on.” The cars going along the bridge were louder and more aggressive as was the rhythmic humming and gurgling of boat engines. It seemed that I was able to listen under water too even though I was not using any hydrophones. The horses seemed closer as I could hear them neighing. The sounds were magnified and the layers within the soundscape were clearer, while imposing on what should have been a tranquil space. However this is what microphones do: they magnify the sounds around us and we can hear the sounds that we may have missed or filtered out. Through the art of recording we can hear the soundscape even clearer and this in turn helps us to understand it better.

When the recordings are imported into a piece of software like Audiosculpt, a sonogram analysis provides a visual representation of the soundscape. The layers of the soundscape can be seen, such as the rumblings of traffic in the lower frequencies and the tweets of small birds in the higher frequencies. As we can see the sounds in the sonogram we can anticipate their arrival, which allows us to hear sounds that we have missed when listening to the recording on its own.

Soundwalks

Rosemary was unable to attend the soundwalk but when we met, I told her about soundwalks and how to do them. After our meeting and the discussions that we had Rosemary did her own soundwalk down by the River Shannon, which is where I took the participants. She told me that after her conversation with me she went for a walk and “I went down with my ears wide open” (Johnson and Porter 2012). Rosemary’s thoughts and feelings about the soundwalk can be heard in the piece at 2:41 when she says “Although you expect it to be a quiet place, when you stop to listen there is so much going on.” I was impressed by her thoughts about her listening experience and was content to know that teaching people about listening and their soundscape was not too difficult (depending on who you meet). Soundwalks change the way people hear and are a fantastic way of introducing people to listening, thoughts about noise pollution and making them aware of the environment around them.

Recontextualizing Sound

While composing this piece I tried to create a balance between processing sounds and retaining their natural characteristics. Some natural sounds are left unprocessed so that the spoken word can be related to a specific natural sound environment.

However they are brought into a new context where they are treated and transformed to enhance the spoken word. Their purpose is to flow with the words and articulate the story. The movement is subtle so that the listener is not bombarded with sound, but can process the words and sounds of the story.

In Kits Beach Soundwalk, Westerkamp uses her voice and narration to draw the listener’s attention to “many of the sonic subtleties of the location” (Young 2008, 321). Similarly, in The Thing About Listening is…, the spoken word guides the listener through the composed soundscape while the rest of the sound material punctuates the spoken word. It is my intention that the spoken word will make the material more accessible to the listener, setting the scene, the space and place.

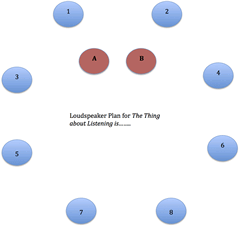

Space and Sound Diffusion

The Thing About Listening is an 8-channel work, composed for a ring of eight loudspeakers creating an immersive listening environment, “an enhanced experience of space” (Barreiro 2010, 291). Multi-channel composition allows the composer to recreate specific soundscapes where the compositional space is extended from stereo to quadraphonic or octophonic. This allows the composer to create a “realistic” version of the original sound environment, especially when field recordings are the material being used.

Even just eight channels of discrete source material creates a convincing soundscape where composed sounds can be localised in the manner experienced in acoustic environments. (Truax 2008, 105)

The approach I have taken is, as Barreiro describes:

[B]ased on a more generalized (or diffused) distribution of the sounds, not concerned with their precise localization. In this case, the identification of spatial regions such as “frontal”, “lateral”, “at the periphery of the space”, “close” and “distant”, for example, are considered to be significant enough to articulate the spatial dimension of a work. With multichannel systems, this generalized or diffused spatial approach can generate sounds that envelop the whole audience, causing the sensation that the sounds are the space. (Barreiro 2010, 291)

My approach may be generalized as discussed by Barreiro but the localisation of certain sounds is also very important depending on the sounds used. Localization of sounds such as birdsong and people’s voices is necessary when working with two- or three-dimensional space to make the space and the virtual soundscape more believable.

I experimented with the location of the spoken word materials, for example placing them in the front stereo pair of speakers with the next phrase coming from the rear stereo pair. However, as the composition developed I felt that the movement of the spoken word within the 8-channel ring disrupted the flow of the piece. Therefore, in the final version of the piece, the spoken word materials now remain fixed in the front stereo pair of speakers, creating an illusion that the narrator is sitting in front of the audience.

When working with spoken word and multi-channel there are some compositional dilemmas that the composer has to deal with. For me, this was in relation to the format of the work. The format is 8-channel and this is how it was composed in the studio. When it is performed in another environment with a circle of eight loudspeakers, the composition remains fixed. I am aware of the acoustic changes in various performance spaces, but the format remains the same.

The issue of sound diffusion caused me to question this format. I experienced this at the MANTIS Festival in October 2013 when I diffused another piece A Bit Closer to Home, which is also 8-channel and, like The Thing About Listening is…, it also features spoken word that remains fixed on the front stereo pair of loudspeakers throughout the work. However when presented with the opportunity to diffuse on the MANTIS 48-channel system, I soon realized that my work could not be adapted to the system and faced many challenges when diffusing during rehearsals. The reason for this was that the spoken word was meant to remain fixed immediately in front of the audience. When diffusing the work, the 8-channel image could be spread across multiple rings of eight loudspeakers, which also included loudspeakers located in the ceiling. At certain points while rehearsing the piece, the spoken word could be heard on the loudspeakers in the ceiling, which disrupted the illusion of the narrator sitting in front of the audience. The solution was to change the format of the piece from 8-channel to 10-channel. The extra two channels were used only for the spoken word so that it would remain fixed and separate from the rest of the material, on a dedicated pair of loudspeakers. Composers working in multi-channel may, for such reasons, need to create several versions of a piece, such as stereo or 8-channel. Barry Truax discusses this:

The variability of the destination environment suggests that not only might one have to design the sound so that it works under various conditions, but also that one might want to create several versions of the piece designed for different media and formats (e.g., quadraphonic or octophonic speakers, FM stereo, stereo CD, headphones, etc.). Each version can be adapted to the restrictions of the medium (e.g., bandwidth, dynamic range, number of channels, etc.). [Truax 2001, 245]

This 10-channel format was used at a concert at DMU in Leicester on 15 January 2013, and I was very happy with the results. I no longer had to worry about moving the spoken word and disrupting the illusion.

Conclusion

When discussing my research and trying to educate people about listening to their environment, a soundwalk is a very useful tool to help the listener understand soundscape studies. The series of events and chance encounters that occurred as result of my soundwalk with Hildegard Westerkamp at the Global Composition Conference in 2012 has had a huge impact on my compositional process and thinking. When I organized my own soundwalk in Ireland I thought it was a great idea. About two days later, I began to panic and thought, “Nobody will show up and they will think the whole idea is crazy.” I persevered and continued with my plans. It only took one soundwalk for me to organize and the people I have met and spoken to as a result have fuelled my creative thinking and process.

I have created two electroacoustic compositions as a result for my PhD portfolio. During performances of these pieces I have had many interesting conversations with people about the works and received some wonderful and encouraging comments. This again has fuelled my creativity and given me more ideas for compositions in the future. Therefore the creative process continues.

Other Outcomes

Aideen Madden, a participant on the soundwalk, wrote an article about her experience in the local Banagher Review, a journal that is published every December documenting all the events held in Banagher over the previous year.

As a result of our discussion and her own soundwalk, Irish poet Rosemary Porter wrote a poem about the sounds of Banagher.

Talking to participants on the soundwalk and discussing the soundscapes of the past resulted in an idea for another piece, A Bit Closer to Home, which was completed in October 2013.

Bibliography

Barreiro, Daniel. “Considerations on the Handling of Space in Multichannel Electroacoustic Works.” Organised Sound 15/3 (December 2010) “Sound <-> Space: New approaches to multichannel music and audio,” pp. 290–296.

Harrison, Jonty. “Sound, Space, Sculpture: Some thoughts on the ‘what’, ‘how’ and ‘why’ of sound diffusion.” Organised Sound 3/2 (August 1998) “Sound in Space,” pp. 117–127.

Johnson, Brian and Rosemary Porter. Personal Interview. August 2012.

Lane, Cathy. “Voices from the Past: Compositional approaches to using recorded speech.” Organised Sound 11/1 (April 2006) “Sound, History and Memory,” pp. 3–11.

_____. “Interview with Trevor Wishart.” In Playing with Words: The spoken word in artistic practice. Edited by Cathy Lane. Manchester: Cornerhouse Publications, 2008, pp. 70–77.

McCartney, Andra. “Sounding Places: Situated conversations through the soundscape compositions of Hildegard Westerkamp.” Unpublished PhD Dissertation. Toronto ON: York University, 1999.

Schafer, R. Murray. “The Music of the Environment.” In Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music. Edited by Christoph Cox and Daniel Warner. London: Continuum, 2004, pp. 29–39.

Truax, Barry. Acoustic Communication. 2nd edition. Westport CT / London: Ablex Publishing, 2001.

_____. “Soundscape Composition as Global Music: Electroacoustic music as soundscape.” Organised Sound 13/2 (August 2008) “Global Local,” pp. 103–109.

_____. “Sound Listening and Place: The æsthetic dilemma.” Organised Sound 17/3 (December 2012) “Sound, Listening and Place II,” pp. 193–201.

Westerkamp, Hildegard. “Kits Beach Soundwalk” (1989). Published on Transformations. empreintes DIGITALes [IMED 1031], 2010.

_____. “Soundwalking.” In Autumn Leaves: Sound and the environment in artistic practice. Paris: Double-Entendre, 2007, pp. 49–54.

Wynne, John. “To Play or Not to Play?” In Playing with Words: The spoken word in artistic practice. Edited by Cathy Lane. Manchester: Cornerhouse Publications, 2008, pp. 78–84.

Young, John. “Inventing Memory: Documentary and imagination in acousmatic music.” In Recorded Music: Philosophical and Critical Reflections. Edited by Mine Doğantan-Dack. London: Middlesex University Press, 2008, pp. 314–332.

Social top