Spectromorphology Hits Hollywood: Morphology, Objectification and Moral Messages in the Sound Design of ‘Black Hawk Down’

Realism has been applauded in recent Hollywood war films such as Saving Private Ryan and Black Hawk Down, not only for their docudrama cinematography and special visual effects, but also for aural sound design. Gates argues that this surface (ie. visual) realism is used to mask thematic moralizing about masculinity and heroism in an ever-increasing patriotic post-9/11 United States. Contemporary combat films focus on the maturation of feminized boys into masculine heroes through war — soldiers who “do the right thing” when faced with moral dilemmas no matter what their orders. Sound and timbral development plays a crucial role in the film Black Hawk Down towards defining, substantiating and sustaining these thematics. Analogous sonic thematics, and their timbral development, are shown in analysis of scenes from the film.

I. Sonic character development

Realism in sound design has increased throughout the 1990s with the advances in digital recording technology, editing software, and surround sound delivery in movie theatres. It is not difficult to deliver bullets whizzing past an audience, theatre shaking explosions, or sounds of objects and bodies being mutilated. The most powerful and effective films in the history of the art, however, are those which go beyond this realism. Film criticism has long been concerned with symbolism, and how a film delivers meaning beyond its surface. A similar criticism has begun to emerge for sound in film, and indeed, the sound design industry has matured to a level that we must begin to consider the role of sound on as profound a level as visuals. Walter Murch writes in the forward of Michel Chion’s Audio Vision:

“...the metaphoric use of sound is one of the most fruitful, flexible, and inexpensive means...” [to achieve the illusion of “completeness”] ...by choosing carefully what to eliminate, and then re-associating different sounds that seem at first hearing to be somewhat at odds with the accompanying image, the filmmaker can open up a perceptual vacuum into which the mind of the audience must inevitably rush.” (Murch 1994, xx)

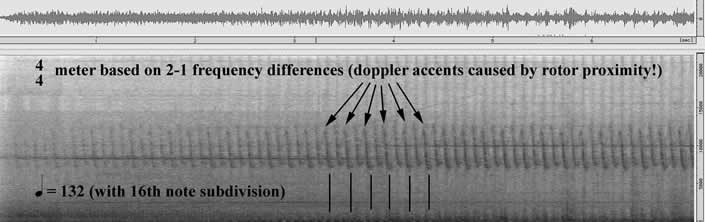

This analysis deals with these associations of sound in Black Hawk Down (Academy Award for Sound Design, 2001), which encompasses a continuum between music, effects and Foley in a total inseparable design. In particular, the helicopter sound, with its primary identifiers of rhythm (amplitude modulation 16th note subdivision with Doppler shift defining “meter”) and broad spectral bandwidth, becomes a character whose sonic development permeates the film from beginning to end. It is even treated as a character whose timbral features and transformations are used to define thematic messages, found throughout the recent Hollywood combat film genre.

II. Background: Combat Film Thematics

Film critics have identified distinct phases of the Vietnam War film: from 1975 to 1980, there was the “tale of moral confusion and the returning vet” like Apocalypse Now (1979) and The Deer Hunter (1978); from 1980 to 1985, there was the “revenge film” like Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985) and Missing in Action (1984); and from 1985 onwards, there was the “realist combat film” like Platoon (1986) and Full Metal Jacket (1987) (McKellar 2001, B6). The returning vet films of the late 1970s established the idea of the Vietnam vet as a victim of the war — one who fought for his country and then was rejected by it. The revenge film of the first half of the 1980s, like Rambo, presented him as a victim but one who had his revenge and through which he could reclaim his masculinity and victory for the United States. The realist combat film of the second half of the 1980s — like Platoon — offered the subjective experiences of the “grunt” in combat and a graphic image of war-as-hell. While war tended to recede to the background of films in the 1990s, the release of Saving Private Ryan and The Thin Red Line in 1998 saw the return of the combat film and marked a new phase of the genre. With the advancement of digital cinematography and computer graphic technology, the new Hollywood war film offers audiences increasingly graphic and violent images of combat — images praised by audiences and critics alike for their realism and authenticity. As critic Stephen Hunter states, “Black Hawk Down is the next worst thing to being there. That’s how real it feels” (2002, C01). The combat sequences dominate the film’s screen time and are unrelenting; viewers have only a moment to come to terms with one shocking scene before being exposed to another. Documentary-style filming, de-saturated colour, and a deafening soundtrack have become the standard for today’s war films. And this is where realism comes up against fiction: while the new Hollywood war film may offer this “true” portrait of battle, this realism merely masks the idealised image of war the film simultaneously purports. The realist combat film of the 1980s presented a political critique of America’s involvement in Vietnam; conversely, the new Hollywood war film does not present a political war but a moral one — and the hero who fights them is the idealistic youth.

In the 1980s, war films were concerned with a crisis of masculinity incited by the American failure in Vietnam, and this crisis was worked through along the lines of gender — masculinity was honoured and femininity reviled: feminised men were either killed off as the more manly men survived, or they too became masculinised. The new Hollywood war film presents a shift away from this revilement of feminised masculinity and offers the idealistic youth as a successful integration of the feminised into masculinity and, as such, represents the ideal hero for the new millennium. The heroes of the new Hollywood war film tend to be played by younger stars like Matt Damon, Josh Hartnett, Ben Affleck, and Colin Farrell — who, independent of their age, look young, boyish, and/or androgynous in appearance. No longer is Vietnam the war that should not have been fought, or U.S. military intervention questionable, because the grunts that put their lives on the line for their country are fighting for the “right” reasons. These films are concerned less with men doing their duty as prescribed by their superiors and more with their following a more important moral code — even if following that code means disobeying orders. The youth is needed as a site for the expression, working through, and resolution — albeit a fictional one — of the themes of the new Hollywood war film: heroism defined through idealism, moral choice, and self-sacrifice in the interests of the brotherhood — the “Army of One”.

Linda Dittmar and Gene Michaud argue that Vietnam war films of the 1980s, like Platoon and Missing in Action, focus on the conflict that arises, not with the enemy, but rather between American men, and it is that conflict that must be resolved through the course of the film (1990, 5). On the other hand, the majority of new Hollywood war films reject this conflict model and, instead, return to the cooperation model of the World War II film — namely that men who work together can overcome any odds. However, the heroes of these films do not just form a bond with one another but consider each other — as the title of the Spielberg-produced TV mini-series suggests — a “Band of Brothers”. The tagline for Black Hawk Down, “Leave no man behind”, is the mantra of many of the new war films as soldiers are willing to sacrifice their own lives for those of their brothers and in service of their country. These thematics are expressed not just at the level of narrative — through dialogue and visuals — but are also clearly expressed within the sound design as well.

III. Sonic Thematics: Timbral Evidence

Contract with Listeners: setting expectations

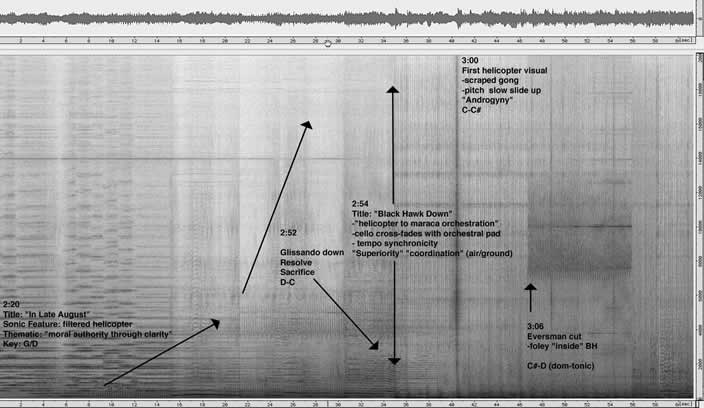

The opening five minutes of Black Hawk Down establishes the “contract with the listener”, laying out before us how the helicopter theme and spectral transformation function within the sound design, and how it underpins notions of “moral authority”, “androgyny”, and the other psychological issues connected to wars of the United States at the turn of the millennium: “resolve”, “brotherhood”, “necessary force” and “technical superiority”. Other thematics treated through sound are “idealism”, “maturation” and “sacrifice”. Three main types of sound development, independent of traditional musical leitmotif themes which the film also has, are featured in the sound design: morphology (further broken down into spectral and timbral morphologies), pitch mutations and amplitude synchronicity. Each of these sonic developments underpin and even define specific ideologies set forth in the film, and each one is intricately tied to the Black Hawk Helicopter sound.

Three Development Methods and Correlative Thematics

1a) Spectral Morphology is expressed through single sound shaping and signifies “moral authority” and “clarity”. Smalley defines spectro-morphology as “...an approach to sound materials and musical structures which concentrate on the spectrum of available pitches and their shaping over time” (Emmerson 1986, p. 61). This definition can be further narrowed into two distinct categories: spectral morphology and timbral morphology: the former being the shaping of the spectrum of a single sound over time, and the latter being the cross morphology between multiple sounds or sound types. The first clear example of spectral morphology occurs during the opening sequence at the title “In late August, America’s elite soldiers, Delta Force, Army Rangers and the 160th SOAR are sent to Mogadishu...” (00:02:20). The wind begins to pulse regularly, obviously forecasting the helicopter sound, but with the high frequencies filtered out. Over the next 20 seconds, the high frequencies are gradually added back. This morphological coloring of sound goes beyond merely introducing the Black Hawk Helicopter, however. The visual images thus far have been of dead and dying Somalis, colorized in a cold, impartial blue, which, along with the sound, transforms into warmer, more true color. As Robert Cogan states in his introduction to New Images of Musical Sound, register drastically effects the brightness of a sound, which is clearly what is perceptually happening here (1984, 12–13). The reverse filtering of both image and sound then, through unfolding clarity signifies “necessity” and “justification” which underpins moral authority and sends the clear message: “never fear WE are here to save the day... to clear things up....”

1b) Timbral Morphology is expressed through multiple sound shaping in combination which, in the beginning of this film, clearly signifies the notion of “androgyny”. The first instance of timbral morphology occurs at the title Black Hawk Down and illustrates this notion. The main instrument sounds like a cello but with timbral qualities of the “ethnic” instrument (also filtered like the helicopter sound) used earlier in the title sequence. Similarly, a scraped gong sound timbrally ushers in the first helicopter visual and corresponding Foley. At this point, the cello cross-fades into the orchestral pad, and the helicopter Foley links to the orchestral maracas through common frequency space, the first sonic link between ground/air co-ordination and superiority also developed throughout the film with sound. Here, the ambiguity and elasticity of quasi-cello sound suggests a pre-disposition to change, an ambiguity of identity, a vulnerability or, as Gates puts it: androgynous character with indeterminate [feminine and masculine] traits.

2) Pitch Mutation also maps onto narrative thematics and is used to signify resolve and sacrifice. These are expressed in two ways: instrumental glissandi in the music, and helicopter flyover Doppler shift. A glissando down (from D–C) in the quasi-cello (00:02:35) signifies resolve to do the right thing (reinforced visually by the title Black Hawk Down and by association-“sacrifice”), while a slow pitch glissando back up (C–D) coupled with the first cut to the main character Eversman inside the helicopter, signifies the edgy androgynous boys going into battle. All of these ambiguities effect an unsettled quality — a constantly moving landscape of sonic properties which clearly maps onto the boyish identity of Eversman, his dilemma about what this all means, and his growing up which is clearly a primary message of the film.

3) Amplitude modulation and synchronicity are sonic techniques present throughout the film to express the notions of technical superiority, ground/air coordination and band of brothers. The first occurrence of amplitude modulation is 15 seconds into the film when the desert wind is subtly but clearly pulsed. It becomes prominent in the exposition, not only when the filtered helicopter sound enters in the above example, but also when we first see Eversman inside the flying helicopter (00:03:00), and the Foley sound is in synchronization with the music. Even the birds are sounding as quarter note triplets against the pulse. Throughout the film synchronicity, asynchronicity and metric modulation between Foley and music are used to underpin psychological notions and increase, or decrease tension.

This one minute segment, with its sonic thematics then looks like this:

Walter Murch writes, again in the forward to Chion’s Audio Vision:

“...the possibility of reassociation of image and sound is the fundamental stone upon which the rest of the edifice of film sound is built, and without which it would collapse.” “...to stretch the relationship of sound to image wherever possible: to create a purposeful and fruitful tension between what is on the screen and what is kindled in the mind of the audience...” (1994, xvix)

“Once you stray into metaphoric sound...the human mind will look for deeper and deeper patterns....and find those patterns, if not at the geographic level, then at the natural level; if not at the natural level, then at the psychological level” (2003, 100).

Clearly in this example, the sound designers are interested in going well beyond the “see it equals hear it” surface level. They make powerful use of these levels of cognition, counting on our ability to make both conscious and subconscious sense out of complex associations of image and sound. The following is a short list of some of the more prominent examples within the first hour of the film for further scrutiny.

| Time | Scene | Sonic features |

| 00:33:22–00:34:00 | McKnight’s Briefing | High pitched whine of helicopter warming up with upward glissando |

| 00:35:26–00:36.00 | Gen. Garrison: “no one gets left behind” | Metric Modulation of helicopter 16ths duplets to triplets |

| 00:53:14–00:58:00 | Ground forces advancing to crash site | Complete tempo consistency and synchronicity throughout entire sequence of cuts (synchresis) |

| 00:51:15–00:52:50 | Super 6-1 shot down | Multiple levels of tempo synchronicity and a-synchronicity |

| 00:53:45–00:53:54 | Steele advising chalk 4 | In tempo clicking links timbre of gunfire to helicopter tempo |

Table 1: further examples of re-association

Of particular interest may be the mantra scene when General Garrsion says: “no one gets left behind”. The combined forces are preparing to leave the base and a metric modulation occurs in the helicopter pulse (00:35:26). The duple subdivision of the helicopter pulse, defined by Doppler shift, is reinterpreted through the rock music to a triplet subdivision. This clearly unsettles the scene which is reinforced when Eversman, speaking of General Garrison, says: “he’s just never done that before”.

Another significant use of sound occurs as the units are flying into the Vacarro Market and all of the salient features thus far described: morphology, pitch mutation and amplitude modulation figure prominently to establish the psychological space of the soldiers going into battle. The sound design objectifies and develops sound in a Schaefferian montage with transformations between helicopter, instrumental, and even bird sounds, based on their trimbral features. This is one of the last contemplative sonic spaces we are given.

After the first crash, there is a five minute segment of scenes in which all sound (music, Foley and effects) are synchronised in a single uninterrupted tempo (00:53:14–00:58:00). Many of these examples are used either to heighten drama or to reinforce the band of brothers notion and also signify the coordination of air and ground forces.

Two examples from this segment show the unity of tempo despite radically different source material. 1st, Cpt. Steele advises Eversman to advance to the crash site. Of special interest here is an in-tempo clicking sound in the fabric of gunfire that transfers the pulse of the helicopter to the ground through rhythm and common frequency space.

The second example shows a unity between music, helicopter Foley and gunfire at the same tempo of the previous example. This synchronicity clearly underpins the notion of technical superiority and air/ground coordination.

IV. Manipulation and Coordination of Diagetic Source

Moral underpinning occurs through diegetic source music during the scene where Eversman explains that he thinks he was “trained to make a difference” (00:17:30). The music playing in the barracks is Die Born, by Days of The New. What drew my attention to this scene was the high frequency clicking of the cymbals which seem to be filtered in just before Eversman speaks. The song text and dialog are as follows:

Song intro: Die Born, by Days of The New

(cymbals) |

Soldier 1: “Listen to this: one Skinnie kills another Skinnie, his clan owes the dead guys clan a hundred camels.” Soldier 2: “Camels...I wouldn’t pay one camel” Soldier 3: “There must be a lot of fuckin’ camel debt.” Is that really true, Lieutenant?” Soldier 1: “Ask Sgt. Eversman...he likes the Skinnies.” Soldier 3: “Sgt. Eversman, you really like the skinnies?” |

I am cold and I don’t know why said you got to keep me warm You will run, run from my eyes they stare you down and make you burn (omitted: I am the king, the king of the jungle) I’m the little dog So the king of the jungle makes me humble I will not die born I will not go down this is not my home For any fears at all any fears at all any fears at all any fears at all |

Eversman: “It’s not that I like ‘em or I don’t like ‘em, I...respect ‘em” Soldier 4: “See what you guys fail to realise is that the Sergeant here is a bit of an idealist. He believes in this mission down to his very bones, don’t you, Sergeant?” Eversman: Look, these people, they have no jobs, no food, no education, no future... I just figure that, you know, I mean, we have two things we can do... We can either help, or sit back and watch a country destroy itself on CNN, alright? Solider 4: “I don’t know about you guys, but I was trained to fight! Were you trained to fight, Sergeant?” Eversman: “Well, I think I was trained to make a difference, Kurth.” |

|

Soldier 1: “Like the man says, he’s an idealist...Wait, this is my favorite part.” |

Keep me running, keep me running wild, keep me innocent |

|

The SAND is hot, it burns my feet I’m a little tired Don’t know what I’m gonna do with this I am gonna run (text becomes obscured by Foley...) Gonna make it worth, make it worth my while, make it worth, worth my while |

Steve Martin: (Movie “The Jerk” on TV) “Stay away from the cans” Shooter: “Die gas pumper” |

It is no accident that the text of Die Born matches so closely with the dialog on the screen, reinforcing the already established thematics of moral authority and idealism of the young US soldiers “doing the right thing” in the desert sand of Somalia that burns the feet.

One might wonder if this is surmising too much from a few excerpts, and yet these careful uses of sound and transformations appear consistently throughout the film. One of the most poignant examples, which drives these messages home, occurs at the end of the film when Captain Steel visits a dying Ruiz (02:10:25). In the background, the Doppler shift of a helicopter flyover (which pitch shifts a major second down) timbrally cross-fades into the orchestral pad (morphology and pitch mutation combined like in the beginning) driving home the main message of the film: sacrifice must be made in order to do the right moral thing no matter what the personal cost. Ruiz’ statement “...don’t go back out there without me” even as he is dying, confirms that androgynous effeminate boys, do indeed grow up in the heat of battle, a message driven home by Zimmer’s orchestration of chiming “death” bells which articulate the orchestral pedal point. Also notice the happily chirping birds in the background even though the scene is set inside, which, through Chion’s concept of synchresis (1994, 63), sends the message that Ruiz is happy to die for his country, and perhaps even that we are happy he is dying for all the right moral reasons. Yet another flyover with Doppler transitions to Eversman and Hoot, who is preparing to “go back in....”

V. Conclusion: Glorification of War

This search of Black Hawk Down for these minute details began for one reason: to draw connections between the timbral composition of electroacoustic music and popular media, where its influences are unmistakable. Indeed, this film shows a common understanding of sound by those who work with it, and a common acceptance of sound transformation by the general public as well. In short, it sets a new bench mark in the evolution of a timbral common practice that has its roots in early practitioners of both electroacoustic and acoustic music of the 40s, 50s and 60s, from Schaffer, Varèse and Berio to Cage and Stockhausen. In this paper, that common practice and understanding goes even deeper into an area many are afraid to tread: what do these sound transformations mean. Recorded sound and film are the perfect media to carry out this discussion because of their ability to simultaneously give us images filled with explicit information while at the same time destabilising what those images mean through paradoxical juxtaposition. The continuum of expression from explicit to implicit and further to totally ambiguous does indeed invite our minds to rush in as Murch says, and hence, the second reason that this exploration continues in Black Hawk Down: a tension between the many positive things a world power brings to the globe and a pacifistic upbringing that these US wars go against. In the case of Black Hawk Down, just as the images and sound are often at odds with each other, these two psychological sentiments are at odds in the most poignant ways.

As Sue Williams says, Black Hawk Down becomes “an astonishing glorification of slaughter that makes the tragedy look like a majestic triumph for the brotherhood of man, rather than a humbling defeat for the United States” (2002, 41). The war films of the 1980s, according to Dittmar and Michaud, used Vietnam vet heroes to unmask the racist, economic, and patriarchal institutions that sustained a war that was seen — by American society at large — as unjustifiable (1990, 4). In contrast, the new cycle of Hollywood war films has no such critique to offer its audiences — no debate about U.S. military intervention, no contemplation of race, gender, and class, or the demonising of the racial “other”. Instead, they offer a relatively uniform glorification of American patriotism and heroism, not unlike the pre-Vietnam World War II film. The wound that Vietnam inflicted on American society seems still not to have healed and events like 9/11 and the War in Iraq have only exacerbated the need for idealised heroes. Rather than exploring America’s failure in Vietnam like the war films of the 1980s, new Hollywood war films like Black Hawk Down choose a fight they can win as their focus. Unlike the Vietnam war films of the 1980s, the new Hollywood war films end with clear-cut heroes and moral — if not military — victories. Sound, on every level speaks these messages as loudly as both the dialog and the images.

References

Chion, Michel. Audio Vision: Sound on Screen. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Cogan, Robert. New Images in Musical Sound. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1984.

Dittmar, Linda and Gene Michaud. ‘Introduction’, From Hanoi to Hollywood: The Vietnam War in American Film. L. Dittmar and G. Michaud (eds.). New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1990, 1–15.

Emmerson, Simon. ‘The Relationship of Language to Materials’, in The Language of Electroacoustic Music, pp.17–40. Simon Emmerson (ed.). New York: Harwood, 1986.

Gates, Philippa. “‘Fighting the Good Fight’: The Real and the Moral in the Contemporary Hollywood Combat Film”, in Quarterly Review of Film and Video 22:4, forthcoming 2005.

Gorbman, Glaudia. Unheard Melodies: Narrative Film Music. London: BFI, 1987.

Hunter, Stephen. ‘Shock Troops: The Battle is Engaged, and so is the Audience, in the Ferocious Black Hawk Down’, in Washington Post, 18 January 2002, C01.

McKellar, Ian. ‘Apocalypse, Then and Now’, in National Post, 10 July 2001, B6.

Murch, Walter. Forward to Audio Vision: Sound on Screen, Michel Chion. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994, vii–xxiv.

___. ‘Touch of Silence’, in Soundscape: The school of Sound Lectures 1998–2001, pp.83–102. Larry Sider, Diane Freeman and Jerry Sider (eds.). London: Wallflower Press, 2003.

Rudy, Paul. ‘Spectromorphology Hits Hollywood: Sound Objectification in Black Hawk Down’, in International Computer Music Conference Proceedings, pp.658–663. Miami FL, November 1–6, 2004.

___. ‘Total Sound in Film: Black Hawk Down, A Case Study’, in Conference Proceedings, 2nd Hawaii International Conference on Arts and Humanities. Honolulu, Jan. 8–11, 2004. (CD-ROM)

Smalley, Denis. ‘Spectro-Morphology and Structuring Processes’, in The Language of Electroacoustic Music, pp.17–40. Simon Emmerson (ed.). New York: Harwood, 1986.

Williams, Sue. ‘Films that Trade on Violence: Black Hawk Down’, in World Press Review 49:4, p.41, April 2002.

Filmography

Apocalypse Now. Dir. Francis Ford Coppola; Perfs. Marlon Brando, Robert Duvall, Martin Sheen. 1979.

Black Hawk Down. Dir. Ridley Scott; Perfs. Josh Hartnett, Ewan McGregor, Tom Sizemore. 2001.

Deer Hunter, The. Dir. Michael Cimino; Perfs. Robert De Niro, John Cazale, John Savage. 1978.

Full Metal Jacket. Dir. Stanley Kubrick; Perfs. Matthew Modine, Adam Baldwin, Vincent D’Onofrio. 1987.

Hamburger Hill. Dir. John Irvin; Perfs. Anthony Barrile, Michael Boatman, Don Cheadle. 1987.

Missing in Action. Dir. Joseph Zito; Perfs. Chuck Norris, M. Emmet Walsh, David Tress. 1984.

Platoon. Dir. Oliver Stone; Perfs. Tom Berenger, Willem Dafoe, Charlie Sheen. 1986.

Rambo: First Blood Part II. Dir. George P. Cosmatos; Perfs. Sylvester Stallone and Richard Crenna. 1985.

Saving Private Ryan. Dir. Steven Spielberg; Perfs. Tom Hanks, Ed Burns, Tom Sizemore. 1998.

Thin Red Line, The. Dir. Terrence Malick; Perfs. Sean Penn, Adrian Brody, James Caviezel. 1998.

Other articles by Gates

Detecting Men: Masculinity and the Hollywood Detective Film. Albany, NY: SUNY Press (in press, 2006).

The Devil Himself: Villainy in Detective Fiction and Film (Co-edited with S. Gillis). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002.

‘Fighting the Good Fight‚: The Real and the Moral in the Contemporary Hollywood Combat Film’, in Quarterly Review of Film and Video 22:4, pp.297–310, October–December 2005.

‘Manhunting: The Female Detective in the Contemporary Serial Killer Film’, in Post Script 24:1, pp.42–61, Fall 2004.

‘Always a Partner in Crime: Black Masculinity and the Hollywood Detective Film’, in The Journal of Popular Film and Television 32:1, pp.20–29, Spring 2004.

‘The Man’s Film: Woo and the Pleasure of Male Melodrama’, in Reading for Pleasure: New Perspectives on Gender, Politics and Interpretation. Special Issue of The Journal of Popular Culture 35:1, pp.59–79, Summer 2001.

Other articles by Rudy

‘Interpolating Electroacoustic Sounds in an Acoustic Context: Analyzing Timbre, Time and Pitch in Íris by João Pedro Oliveira’, in Journal SEAMUS, Vol.18 No.2, January 2006.

‘Separation Anxiety, Metaphoric Transmutations from a Paradoxical Biological Instrument or: What is a cactus doing in our concert hall?’, in Organized Sound, Vol.6, No.2. Cambridge University Press, August 2001.

‘Spectro-morphological Diatonicism: Unlocking Style and Tonality in the Works of Denis Smalley Through Aural Analysis’, in eContact! 6.4, Analyse Électroacoustique / Analyses of Electroacoustics. Also published in Journal SEAMUS, Vol. XVI, No. 2, pp.18–27, Fall/Winter 2001.

‘Timbre, Time and Pitch Strategies in Íris by João Pedro Oliveira’, in Contemporary Portuguese Composers, Edicões Atelier de Composição, pp.65–84, December 2003.

Social top